Alan Finney, ‘godfather of Australian cinema’, passes the AFI baton

By Karl Quinn

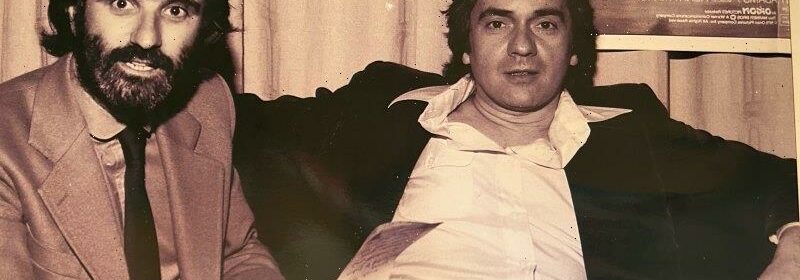

Alan Finney, right, with the actor, comedian and musician Dudley Moore c1979 during the Australian press tour for 10.

Alan Finney has brought props with him to lunch at Cosi, a slick Italian eatery on Toorak Road, South Yarra. The place is just a few minutes walk from the home of the man Russell Crowe calls “the godfather of Australian cinema” – which is handy because he doesn’t drive, and never has.

I’ve barely sat down before Finney has started pulling artefacts out of his bag. There’s the piece he wrote on Sophia Loren for the Melbourne Uni student mag Farrago in 1965, about midway through the law degree it took him nine years to complete and which, he says proudly, “I’ve never used”.

There’s a CV of sorts that lists his acting credits and production roles on some of the first films of the Australian New Wave (Alvin Purple, Stork, Eliza Fraser), his work with the Australian Film Institute (AFI) and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, and his actual day jobs as head of marketing and distribution at Village Roadshow, as managing director of Disney’s Buena Vista International, and as co-founder of streaming platform OzFlix.

After 12 years as chair of the Australian Film Institute, Alan Finney has stepped down. He will, however, remain a board member.Credit:Eddie Jim

There are photocopies of some of the ads he created, even of the session time listings that used to fill the entertainment pages of publications such as this one before the internet changed everything.

In more than half a century in the Australian film industry, Finney has been an actor, a producer, a distributor and a marketer par excellence. He made hits of some of this country’s biggest movies, and he made famous friends too. His house is lined with photos of him with some of the stars he had over to dinner: Robert Duvall, Bette Midler, Sean Connery, Bo and John Derek, Anthony Hopkins, Whoopi Goldberg (with her then boyfriend Rutger Hauer), and Dudley Moore among them. But for now the shot of him with Martin Scorsese has, sadly, gone missing.

In 1975 he went to America with Jack Thompson to talk up the movie Petersen, which the Americans renamed Jock Petersen, much to Finney’s distaste. “They were mainly interested in the fact that he lived with two sisters,” Finney recalls. “Jack was very good with the media, he was a star straight out of the gate.”

George Lucas and Stanley Kubrick used to have him on speed dial. He was close to British filmmakers Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson and Jim Sheridan. He counts Stefan Elliott (Priscilla), George Miller (Mad Max) and Oscar-winning actor Geoffrey Rush among his close friends. Romper Stomper writer-director Geoffrey Wright (“Nice man. I like him”) is a de facto son-in-law (Wright has a child and lives with one of Finney’s three daughters). Deborra-Lee Furness was once his secretary.

For more than 50 years, Finney has been a player. But now, at 77 and with a serious health issue that will soon see him spend up to three months in hospital, it’s time to pass the baton to others.

“There are people that have got more regular contacts, more awareness of the local market – in other words, they’re more relevant,” Finney says of his decision to stand down as chair of the AFI after 12 years, during which time he helped create a professional membership wing (the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts) and reshape its awards night (as the AACTAs) while also expanding its engagement with regular lovers of Australian film through year-round events and screenings.

With Jack Thompson in the mid-1970s.

He leaves it in good shape, he insists. “The AFI now is part of a very vibrant local scene,” he says, handing me another sheet of paper with potted bios of the board, including new chair Keith Rodger (a producer) and deputy chair Margaret Pomeranz. “I’ve enjoyed it immensely, but I want the organisation to be in the very best hands because it deserves to be and needs to be.”

We’re eating in the back room of the restaurant, where the walls are lined with pictures of the Amalfi Coast and one side of the menu features the artwork for Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. I’ve ordered scallops with roasted cauliflower puree to start, and a ridiculously fluffy gnocchi with pork sausage and mushrooms for the main. He’s ordered the gnocchi too, but with bolognese sauce; it’s not on the menu, but the kitchen happily obliges.

Finney has lived and breathed cinema since long before he landed his first job in the business. His parents had their own seats at the Palais in St Kilda and went every Saturday night; as a little kid, he took their seats for the Saturday matinee. “There was the newsreel, then there were the cartoon shorts, then there were normally two features,” he recalls fondly, instantly drifting back to a time when cinemas were picture palaces, and plentiful.

In his tweens, he joined a choir in a church across the road from another picture palace (this one, at least, still standing and screening movies today). “Between weddings on a Saturday I’d rush across to the Astor and see part of the film, then rush back to the church for the wedding, so I could get paid,” he says.

It was never about what was playing, he insists, but rather the whole experience: “I didn’t choose films. I chose to go to the cinema.”

It was perhaps inevitable that he would try to make this passion a career. In his teens he became an usher (each of his four children did the same in their own teens), and then in his second year at uni he discovered the film society, which promptly took over everything else (and explains why it took so long to finish his degree).

Cosi’s scallops with roasted cauliflower puree.Credit:Eddie Jim

“We had Tuesday afternoon short films, Wednesday afternoon matinees, we pioneered the idea of the Friday late show, and we had festivals. In a funny way I was in film exhibition as a student, that’s what we were doing. It was amazing.”

After graduating he worked as a part-time teacher in Melbourne’s west, and through a fellow teacher landed his first job at Village Roadshow, writing study guides. It was 1969 and a case of right place, right time.

Finney had been involved in La Mama, the tiny Carlton theatre that launched the careers of Jack Hibberd, David Williamson, Graeme Blundell and others. In the first two years after it was launched in 1967 by Betty Burstall after she and her husband Tim had been inspired by the off-Broadway scene in New York, the boutique theatre staged 25 original Australian works, and the response was enough to suggest the time might be right for Australian filmmaking too. “People used to come to La Mama to see Australian actors and actresses performing Australian stories,” says Finney. “So why not on screen?”

At Roadshow, he found a company that felt the same way. Soon he was operating as a producer – he was not especially hands-on, he insists, “but I was always honest” – and occasionally cropping up in small roles. Much as he loved the limelight, he admits his best performances came “when I didn’t show up”.

There was no Australian filmmaking to speak of in 1969. Tim Burstall’s Stork (1971) and Alvin Purple (1973), in both of which Finney had small roles – helped prove audiences were ready for it. “It was great because when people got to the cinema they saw their culture on the screen, they had their language in their ears,” he says.

Within a few years, the movement that would eventually be dubbed the Australian New Wave was well underway, and Finney was playing his part behind the scenes. Over the next couple of decades his marketing nous helped make successes of some of Australian cinema’s most beloved films – Breaker Morant, Gallipoli, Mad Max, Romper Stomper, Muriel’s Wedding, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and The Castle among them.

On the opening weekend of a film, he says, he would always go to the cinema to see how it was playing with a paying audience. “If they stayed through the credits, it worked. That was the most important part of the whole thing.”

The bill, please.Credit:Karl Quinn

So much has changed in the industry since he started. Digital projection, the rise of streaming, piracy (the form of it, not the fact it exists: in the old days they had to guard against thieves who would steal the film canisters containing a new release on the night they were dropped off outside the cinema). The fact Australian talent is now so well established at every level of the business, at home and abroad.

The one thing he thinks hasn’t changed, though, is the experience of watching a movie in a theatre. “Seeing a film in the presence of 400 other people is very different to sitting at home and watching it,” he says. “The cinema experience still delivers, when it delivers, in such a powerful and unique way. Video didn’t kill cinema, and I don’t think streaming will.”

Had things played out a little differently, Finney might never have gone into the business at all. “I was going to join an insurance company, because my dad and brother were in the insurance business,” he says. He was due to start a job in January, but then he landed a Commonwealth scholarship out of school and suddenly university became an option.

Does he ever look back and think “if only I’d done insurance after all”?

“No, no,” he says, laughing. “Nor acting. No.”

The AACTA awards are on 10 on Wednesday, December 7, at 7.30pm, with an encore screening on Foxtel’s Fox Docos on Saturday, December 10, at 7.30pm.

Email the author at [email protected], or follow him on Facebook at karlquinnjournalist and on Twitter @karlkwin.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article