Healing seagrass ‘scars’ to make Sydney Harbour cleaner and clearer

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

A restoration project that includes transplanting an ancient seagrass species and installing skeletal “fish pods” across Sydney Harbour is the centrepiece of a blueprint to rehabilitate urban estuaries across the world.

By revamping entire marine landscapes, or “seascapes”, rather than individual patches of habitat, researchers aim to boost fish populations and create cleaner, clearer water in the harbour fringed by Australia’s largest and densest city.

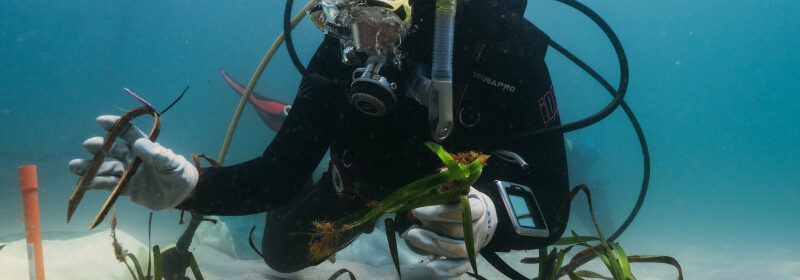

Marine scientists use washed-up strands of Posidonia seagrass to restore damaged meadows.Credit: Woody Spark – Grumpy Turtle Films

“Before, marine conservation was all about protecting what we have,” seagrass expert at the University of New South Wales Professor Adriana Verges said. “Now we’re realising that’s just not enough. We need to not only protect what we have, but restore what was lost.”

Verges is one of the scientists driving Project Restore, a $4.5 million restoration project led by the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS).

The project is part of Seabirds to Seascapes, the world’s largest harbour rehabilitation program. The state government program aims to combat the impact of 250 years of urbanisation on marine ecosystems, support wildlife such as seals and little penguins in the harbour, and cleanse seafloor sediment contaminated by industrial waste.

In two experimental sites in the harbour, marine scientists will install living seawalls and fish pods – artificial structures that provide protective nooks for fish, seahorses and oysters – alongside rehabilitated seagrass meadows in a world-first holistic strategy that connects different underwater habitats.

One part of the project seeks to restore the harbour’s meadows of Posidonia, one of the world’s largest and slowest-growing seagrasses.

A pregnant endangered White’s seahorse on a Posidonia strand off Camp Cove Beach.Credit: Clayton Mead

A 180 kilometre, 4500-year-old swathe of Posidonia in Western Australia’s Shark Bay makes up the largest plant on the planet. But in Sydney Harbour, the ribbon weed is on the brink.

Boat mooring chains have devastated 130,000 square metres of seagrass in NSW by scraping along the bottom of bays and creating “scars” that take two decades to recover.

To counter this destruction, Project Restore will trial the installation of 16 seagrass-friendly moorings – which have tethers that float above the sand – and restore meadows destroyed by dragging chains.

“It’s really a critical time because right now, there’s still enough Posidonia that we can build on and there are still some healthy meadows near Sydney, but they are declining really fast,” Verges said.

The plant can reproduce sexually but mostly expands slowly by self-cloning. It can take a year for the plant to create a new shoot.

“It’s a strategy that has served the species well. It’s been able to survive through millennia. But with the kind of stressors that we’re subjecting the species to now, through urbanisation and climate change, it may not be enough.”

Verges had restoration success in Port Stephens, where Operation Posidonia recruited a “storm squad” of citizen scientists to collect strands of washed-up seagrass that were used to restore and create new meadows.

She plans to use a similar approach to transplant seagrass from Port Hacking and Pittwater into Sydney Harbour, including at a proposed site near HMAS Penguin at Balmoral.

Project Restore will trial 16 seagrass friendly boat moorings, which have floating tethers rather than chains that drag along the sand and create seagrass “scars”.Credit: Operation Posidonia

Seagrasses provide critical habitat for fish species such as snapper in the early months of their lifecycle and secure particles in sediment, making surrounding seawater cleaner and clearer. They’re also a major carbon sequestering force.

“If you were to put in a core down through a seagrass meadow, it’s a bit like an iceberg,” Verges said. “You can actually go back in time … one metre of Posidonia [sediment] would be about 1000 years. That’s all the carbon that has accumulated throughout the millennia.”

Project Restore will launch officially next month. Meanwhile, project manager Dr Paco Martínez-Baena is engaging with communities around the harbour to help choose sites for seascape restoration.

“They are the ones who are in the harbour all the time, fishing, snorkelling, swimming, enjoying the harbour,” he said.

“We’re really positive and really hopeful that the community is going to back us up, and we’ll be able to make it happen.”

A guide to the environment, what’s happening to it, what’s being done about it and what it means for the future. Sign up to our fortnightly Clear Air newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Environment

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article