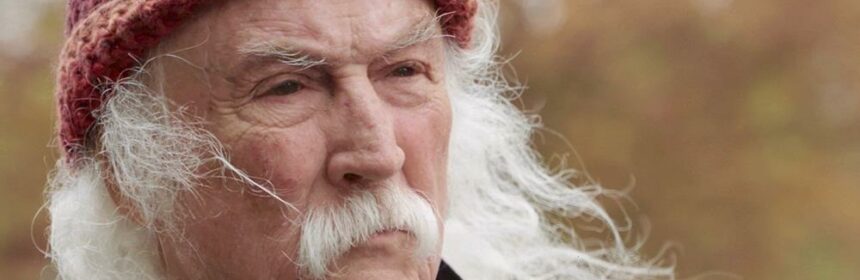

How David Crosby and the Screenwriter of ‘Jaws’ Almost Made an Apocalyptic Hippie Movie in 1971

David Crosby, the legendary musician who died Thursday at the age of 81, grew up in the entertainment industry. His father, Floyd Crosby, was a prominent cinematographer with credits that ranged from “High Noon” and “From Here to Eternity” to “Beach Blanket Bingo” and the TV series “Maverick.”

David Crosby had his own moviemaking ambitions over the years. One effort got close to going before the cameras in 1971 — until United Artists gave Crosby an eleventh-hour ultimatum that did not sit well with his new manager at the time, David Geffen.

The movie had the working title of “Family.” Crosby signed a deal with UA to produce and write the score for the film, which was to be written and directed by Crosby’s good friend Carl Gottlieb. Gottlieb would make a splash as a screenwriter in 1975 when “Jaws” hit big at the box office. Back at the start of the Me decade, Gottlieb and Crosby worked closely together on the story and screenplay that sounds appropriately out-there, given the era.

“It was kind of a hippie idyll,” Gottlieb told Variety of the vision for “Family.” “It was basically a dawn-til-dusk, group-eye-view of a post-apocalyptic world in which an extended family group is moving. Within the group there’s old people, young people, babies and horses and all that stuff. It was meant to be a documentary about a non-existent world.”

As reported in the April 6, 1971, edition of Daily Variety, “Family” was set to begin filming in Oregon in May 1971. The greenlight for production from UA was real, Gottlieb recalls, but then hammer came down. UA asked Crosby to put up the publishing rights to his songs as collateral against the budget for the movie. Geffen wisely advised his client to walk away.

“The studio wanted David to put up his music for collateral. David Geffen, who had a real understanding of music publishing, said ‘No way are we going to do that.’ So the movie never got made. We packed everything and went on about our lives,” Gottlieb said.

Crosby and Gottlieb by that point had taken an office in Los Angeles and were in pre-production, working on casting and costumes and such. They never got to the point of making offers to actors. Gottlieb still has the script and other material from the project in a drawer somewhere.

Crosby had a “real vision of what he wanted the movie to be,” Gottlieb said. “We got paid for writing the screenplay. We were getting ourselves all organized for production. But David would not mortgage his music.”

Gottlieb and Crosby first met in San Francisco in 1963, when Gottlieb was managing an improv comedy club and the Byrds were the house band down the street at a nightclub called the Peppermint Tree. They had recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” the Bob Dylan tune destined to become the Byrds’ first hit, but it hadn’t been released yet.

Gottlieb and Crosby’s friendship endured after the Byrds headed for L.A. and stardom. Gottlieb worked with Crosby on two biographies, 1988’s “Long Time Gone” and 2006’s “Since Then.” Gottlieb interviewed dozens of people from Crosby’s past for the first book and credited the musician with being open to telling the truth about his colorful life and for being introspective.

As a person, Crosby “was difficult,” Gottlieb acknowledged. “He’d always been difficult. Opinionated and firm in his opinions and in defending them. He was not one to easily compromise.”

The “Long Time Gone” book was an important project for Crosby after his release from a Texas prison in 1986 after serving five months on drug and weapons charges. Gottlieb was one of very few people to visit Crosby during his time in prison, which had a profound impact on the musician’s life.

“Crosby wanted to wait until he was sober for a year before he wrote about it,” Gottlieb said.

Crosby addressed sobriety and played off his image as someone who had seen the downside of drugs and alcohol in his 1993 and 1996 cameo appearances on “The Simpsons.” “He was easy to direct,” recalled “Simpsons” executive producer Al Jean. “He came in and hit his marks. We were all such big fans of (Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young). When we knew we needed someone to be a funny presenter at the Grammys (in the episode), we thought of him.”

In addition to collaborating on the biographies, Crosby and Gottlieb also kicked around ideas over the years for other movie projects. But nothing came as close to getting off the ground as “Family.”

“We collaborated on a few other projects. We just worked well together,” Gottlieb said. “We had a picture we wrote together about a World War II German submarine that had been stashed away in South America since 1945. Greenpeace finds it and uses the submarine to go out and combat whalers.”

Gottlieb and Crosby stayed in close contact over the years, speaking most recently about a month ago. Although Crosby was notoriously cantankerous, Gottlieb said he was a loyal and generous friend who grew more comfortable in his own skin as his life went on.

“He was self-deprecating to a fault. He could joke about being fat and gray and old and aging,” Gottlieb said. “But his voice was this miracle that never changed. He had his voice that one constant in his life…I used to say he was going to wind up being the Pavarotti of rock ‘n’ roll because he had that big strong tenor voice.”

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article