How your ghostwriter can come back to haunt you

My late friend Clive James was a prolific emailer. One of the trickiest things about corresponding with the great man was trying to recommend books to him that he hadn’t already read. It was like walking a tightrope, which you could fall off in two ways.

One way was to recommend a book so well-known that you would look like a rube for thinking anyone hadn’t read it. The other danger lay in recommending something that was obscure for good reason – i.e. because it was tripe.

I once thought I’d found the ideal needle-threading recommendation for him: Open, the 2009 autobiography of Andre Agassi. For starters, the book was freakishly good. It was also fairly obscure, at least in literary terms. Recommending it would not be a gaffe on par with recommending, say, War and Peace. Seriously, what were the odds that Clive James was already an aficionado of Andre Agassi’s prose?

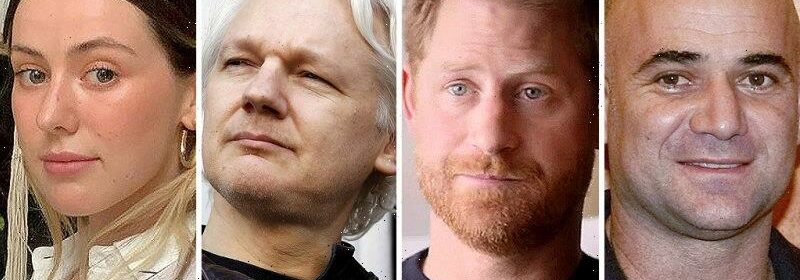

Andre Agassi, Prince Harry, Julian Assange and Caroline Calloway have all made use of ghostwriters.

But he was. On the Agassi issue, Clive was way ahead of me. He’d read the bald maestro’s book when it came out, and he was a big fan. He gave Agassi high marks for his general sensitivity – and for confirming that Jimmy Connors, behind the scenes, was exactly as obnoxious as he seemed on TV.

After the Agassi incident, I gave up trying to catch Clive out with left-field literary recommendations. It was like trying to get an ace past Agassi himself.

Hidden away at the back of Agassi’s book was a salute to its ghostwriter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist J. R. Moehringer. “I asked J. R. many times to put his name on this book,” Agassi wrote. But Moehringer wouldn’t have it. He insisted that the story the book told was Agassi’s, and nobody else’s name belonged on its cover.

Agassi let his ghost have his way, but paid tribute to him in the book’s acknowledgments. “This book would not exist without my friend J. R. Moehringer,” he wrote. It sounded like a cliche, but it was clear that Agassi literally meant it.

Julian Assange’s ghostwriter Andrew O’Hagan came back to haunt him.Credit:Getty

Not that the peculiar excellence of Agassi’s book was all down to Moehringer. It also had a lot to do with Agassi’s own high standards. For instance, it was Agassi himself – not his agent or publisher – who had the acumen to handpick Moehringer to ghost the book. After reading Moehringer’s memoir The Tender Bar, Agassi knew that Moehringer was just the man he needed to give his story the right shape and sound – to write the book Agassi would have written himself, if he’d spent his life learning to tame words instead of tennis balls.

Back then, Moehringer was not a household name. He still isn’t, even though everyone in the world is currently talking about his latest book. It’s called Spare, and its nominal author is – in case you haven’t got wind of this – Prince Harry. Moehringer’s name doesn’t appear on the cover of Spare. Neither does much else, apart from the giant self-pitying face of the chronically downtrodden prince.

Andre Agassi with his memoir Open.Credit:Getty

Nevertheless, it’s common knowledge that Moehringer ghosted the book. Back when the contracts were signed, it was widely reported that Moehringer would be getting US$1 million ($1.43 million) for his troubles. Harry got $20 million, which he’s vowed to donate to charity, assuming he can find one that caters to people even more hard done by than himself.

For all I know, Moehringer gets a hearty shout-out in the acknowledgements of Harry’s book. To find out for sure I would have to buy it, and I’m not going to do that. Waging his insufferable pre-publicity campaign for Spare, Harry finally seemed to prove that there is a hard limit to the public’s appetite for him. He presented the rare spectacle of a man flying too close to the sun while jumping the shark.

As long as publishers keep commissioning books from people who have no idea how to write them, the art of ghostwriting will thrive. There are three basic kinds of ghostwriter. There’s the old-school credited ghostwriter, whose name is frankly revealed on the cover.

Then there are the top-secret ghostwriters, for whom receiving no credit is part of the deal. In 1957, when John F. Kennedy accepted the Pulitzer Prize for his non-fiction book Profiles in Courage, he somehow forgot to mention that the work had been heavily ghosted by his speechwriter Ted Sorensen.

Social media influencer Caroline Calloway.Credit:Instagram

Unacknowledged ghosts like Sorensen get no glory, but the hush money can be good. I may or may not have done this kind of uncredited ghostwriting myself. If I had, I wouldn’t be allowed to tell you.

Then there’s a third category of ghostwriter – a category that Moehringer pretty much invented. Moehringer is the ghostwriter as star. He’s so good at what he does that the people who use him want everyone to know he’s involved, whether his name appears on the cover or not.

Ghostwriting relationships don’t always go so swimmingly. In 2010, Julian Assange accepted £600,000 ($1.05 million) from a British publisher to write a memoir. To ghostwrite the book, the publisher hired the Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagan.

Working to a tight deadline, O’Hagan did his best to coax a book out of Assange. But Assange was recalcitrant. O’Hagan found it excruciatingly hard to make him sit down for interviews, or otherwise commit to the work. And when O’Hagan finally knocked up a manuscript, Assange refused to sign off on it.

This was a big tactical blunder on Assange’s part. The publishers issued the book anyway, under the title Julian Assange: The Unauthorised Autobiography. Then O’Hagan published a long tell-all essay about the affair called Ghosting, which later reappeared in his collection The Secret Life.

The essay let many more cats out of the bag than O’Hagan would have liberated if Assange had stayed on his good side. Assange “is thin-skinned, conspiratorial, untruthful, narcissistic,” O’Hagan wrote. He “doesn’t understand other people in the slightest.” Certainly he didn’t understand O’Hagan. “He thought I was his creature and he forgot what a writer is, someone with a tendency to write things down and perhaps seek the truth.”

When the relationship between subject and ghost goes pear-shaped, juicy revelations follow. It happened again in 2019, when the Instagram influencer Caroline Calloway fell out with her longtime ghostwriting partner Natalie Beach.

For years, Beach had co-written the captions for Calloway’s Instagram pix. Then the pair tried to collaborate on a full-length Calloway memoir, for which a credulous publisher had laid down a six-figure advance.

When that project imploded, Beach published an essay entitled I Was Caroline Calloway, in which she spilled the beans about the confected nature of Calloway’s online persona. After years of working as Calloway’s underloved ghost, Beach was already a powderkeg of resentment. All that remained was for Calloway to make the mistake of lighting the fuse.

“No man is a hero to his valet,” said Napoleon, or one of his uncredited writers. Similarly, few pseudo-authors are heroes to their ghosts. When Donald Trump ran for president in 2016, the ghostwriter of his 1987 book The Art of the Deal felt bound to warn America that Trump was a dangerous man, whose election might “lead to the end of civilisation.” Trump was elected anyway, perhaps because his fan base did not view the end of civilisation as a bad thing.

To date, Moehringer has never gone rogue and told the unvarnished truth about any of his subjects. In the case of Spare, he’s got a million American reasons to keep his mouth shut. That’s 1.43 million Australian reasons. We can only imagine the book Moehringer would have written if Harry had ever made the mistake of upsetting him. Now that’s a book I’d want to read.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article