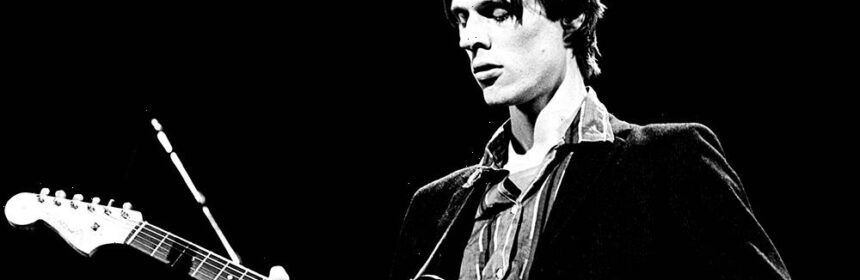

In Praise of Televisions Tom Verlaine as Post-Psychedelic Trailblazer Forever Linked to New York City

“A kiss of death, the embrace of life.” — “Marquee Moon”

The notice came in the form of a Facebook post with a broken heart emoji. “Rest in Peace, Tom,” wrote CBGB’s veteran Brooke Delarco. Tom Verlaine (ne Thomas Miller) was gone at a way-too-young 73 from prostate cancer.

Verlaine’s passing — officially announced, appropriately enough by Patti Smith’s daughter Jesse Paris to the New York Times — hit particularly hard given the fact my own rock critic career launched 46 years ago — March 24, 1977, to be precise — with a Soho Weekly News review of Television’s debut album, “Marquee Moon.” It began with a quote from John Lennon (“Talking is just breaking up sound into little pieces”) and continues to an opening paragraph that remains my only appearance in Wikipedia: “Forget everything you’ve heard about Television, forget punk, forget New York, forget CBGB … hell, forget rock and roll — this is the real item.” I was paid the not-so-princely sum of $5 for my efforts.

Comparing it to the New York Dolls’ lack of success outside of New York, I thought “Marquee Moon” would be the album to carry the torch for a commercial breakthrough after the late A&R maven Karin Berg signed the band to Elektra, where they remained for two albums, including the follow-up “Adventure,” released a year later.

Television’s inclusion of such Nuggets punk prototypes like the Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction” and the 13th Floor Elevators’ “Fire Engine” in their sets was also enticing to someone of my age, just two years younger than Verlaine. But as rockcrit emeritus Robert Christgau noted, “[‘Marquee Moon’] wasn’t punk. Its intensity wasn’t manic; it didn’t come in spurts.”

My review said something similar, “Television is a jamming band that has more in common with Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grateful Dead or Love than with either the Ramones or the Velvet Underground… T.V.’s style is more post-psychedelic than punk. This music is unthinkable without the LSD experience but, unlike the Dead, it deals (without nostalgia) with the aftermath of psychedelia… what happens to those who have left behind acid, yet remain mired with its contradictions.”

A stubborn Verlaine resisted my attempt to characterize it as such in our numerous conversations for the New York Rocker. Verlaine admitted he was more influenced by sax players like Albert Ayler and John Coltrane, while hearing a record by Stan Getz in middle school led him to give up piano in favor of the horn. Hearing the Rolling Stones’ “19th Nervous Breakdown” led him to the guitar.

“I understand all… I SEE NO/destructive urges…I SEE NO/It seems so perfect/I SEE NO EVIL!”

I returned to New York City in 1974 from my undergraduate years at Colgate to go for my MFA in film criticism at Columbia, with the late auteurist critic Andrew Sarris. That’s where I first met Charles Ball, the brother of a friend of a college roommate, and the co-founder of ORK Records with Terry Ork, the manager of Cinemabilia, a movie book store on 13th Street, where both Verlaine and Richard Hell were employees. My first purchases upon returning to New York were Patti Smith’s “Piss Factory” single on Mer, and Television’s two-sided ORK 45, “Little Johnny Jewel.” That would change my life.

As a film student, I appreciated the movie references in Television’s albums, “Prove It” is a noir detective story whose plot shifts allegiances with each successive verse; “Friction” is about the roots of narrative, the tension between listener and talker, how truth becomes fiction through friction; while album closer “Torn Curtain,” the name of a Hitchcock film, notes how the show must go on, even if the players fatally hesitate, or as I put it, “permitting us a privileged glimpse behind the scenes of an ongoing world.”

By the time of “Adventure,” the handwriting was on the wall: “[The album] takes you, not to places unknown, but to places so familiar they may seem boring. But as in the films of Max Ophuls (you can hear the Sarris influence here), these familiarities are what we will miss most when we are no longer here. Living in the material world has certainly had its effects on Television; one hopes they continue to function in it rather than proceed to withdraw into an isolated existence — no matter how pristine.”

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened. After jettisoning both Richard Hell and, eventually, Richard Lloyd, two collaborators who were also junkies at one time, Verlaine continued to retreat, releasing the 1992 self-titled album on Capitol, as well as a series of solo efforts. He continued to tour with guitarist Jimmy Ripp — who was reportedly by his side with Patti Smith when he passed — and just finished a European tour supporting Billy Idol.

His death comes as a shock — it was so sudden I hadn’t even prepared a morgue piece like I’d done for so many aging rock ‘n’ rollers. Tributes came in from the likes of R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, Flea, Billy Idol, former bandmate Richard Lloyd, Richard Barone and Patti herself, whose writing about the band in Rock Scene and Creem originally piqued my interest.

“Dearest Tom,” his one-time partner and girlfriend posted on Instagram. “The love is immense and forever. My heart is too intensely full to share everything now, and finding the words is too deep of a struggle.”

I know what she means. Writing about “Adventure,” I noted, “The world Verlaine and company have created is an ephemeral one, lost in a morass of acid-influenced counterculture ideals and ideas, sunk beneath a misguided search for a perfection that can only exist in art.”

Rest in peace, Tom. Your work will live on.

“This case that I’ve been working on so long / So long… This case is closed.”

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article