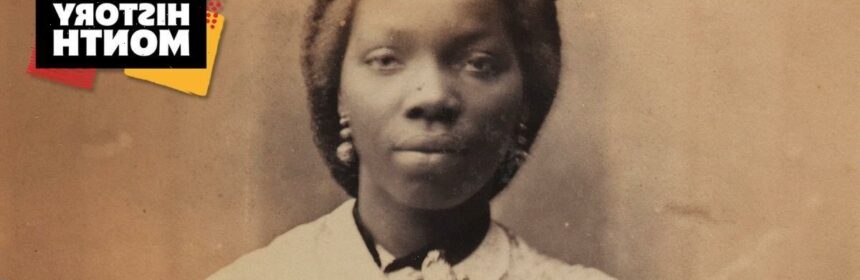

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: The little girl from Africa 'gifted' to Queen Victoria

She is the African Princess you’ve probably never heard of.

Born into violence and shipped out to opulence, given to Queen Victoria as a gift and placed in a gilded cage, Sarah Forbes Bonetta’s life story was so fantastical, even her own descendants doubted its authenticity.

However, it wasn’t fiction, but fact.

Sarah, who was born in Dahomey, West Africa, in 1843, started life as a baby called Omoba Aina. Tragically, her parents were killed by slave-trading ruler King Ghezo, a tyrant who liked to practice human sacrifice.

Ghezo kept the little girl captive until Royal Navy Captain Frederick Forbes – who was on a mission to convince the King to end his involvement in the slave trade – discovered Sarah.

Frightened for her life, the Captain convinced the King to allow him to take the seven-year-old child back to England as an offering for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was simply listed among the gifts as ‘a captive girl’, alongside a footstool and a keg of rum.

Forbes renamed her Sarah – Hebrew for ‘princess’ – and gave her the surname Forbes after himself, and Bonetta in honour of his ship.

They made the perilous journey back to British shores in 1850, where Queen Victoria was delighted by the little girl and kept her on as a protégée, giving her a home, healthcare and education.

From there, Sarah went on to live a spectacular life of luxury and riches as a member of the aristocracy – however, none of it was within her control.

Historian David Olusoga describes Sarah as ‘a woman who has been rendered historically mute, whose names were given to her by others, and yet whose story took her to the centre of the British world system’.

Her tale captured imaginations at the time and continues to do so today. Sarah Forbes Bonetta has been painted by Hannah Uzor, depicted in ITV’s drama Victoria and she was the inspiration behind the novel Breaking the Maafa Chain by author, actor and director Anni Domingo, published last year.

’The history of Black people in England didn’t start with Windrush,’ Anni tells Metro.co.uk. ‘We’ve been here in England for centuries. There were Black people in England during the Henry VIII period and the Elizabeth I period. I wanted to show this young girl through her own eyes, to see what was happening politically, as well as socially, in England in Victorian times.

‘It is important to tell these stories now in this social moment, because even though she was taken on by the Queen and looked after, she was no freer than a slave on a plantation. The fact that she was treated as a princess does not mean that she was free.’

Anni explains that she wanted to reframe Sarah as part of a wider discussion about how we understand identity and history: ‘We have to learn about some of our history in England and what was happening, not just always looking to America when it comes to the Black gaze.

‘We study Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, but we should also be studying people like Sarah, and what that means to society. Was she being exoticised? There are a lot of questions that can be asked.’

Sarah – also affectionately known as Sally – was a talented musician and bright as a button. When she fell ill in 1851 she was sent to Freetown, Sierra Leone for education.

As David Olusoga says in BBC Radio 3 podcast, The Essay: ‘There was at the time, a prevailing belief that the damp and cold of the European climate was potentially fatal to Africans who were exposed to it for extended periods. When Sarah acquired a cough, it was decided that she should be sent to Africa and educated there.’

The young girl continued to be moved around throughout her childhood; from Africa, to Kent, to Brighton, before being married in England to a Sierra Leone-born merchant, James Pinson Labulo Davies at the age of 19, who she barely knew.

Sarah wrote in a letter: ‘Others would say “He is a good man & though you don’t care about him now, will soon learn to love him.” That, I believe, I never could do. I know that the generality of people would say he is rich & your marrying him would at once make you independent, and I say ‘Am I to barter my peace of mind for money?’ No – never!’

Nonetheless, the pair were wed under the Queen’s watchful eye on 14 August 1862 in a lavish ceremony that included 10 horse-drawn carriages and 16 bridesmaids. The wedding party was made up of ‘white ladies with African gentlemen, and African ladies with white gentlemen’, according to newspaper reports at the time.

The couple returned to Sierra-Leone and Sarah’s first-born daughter was named Victoria after the Queen, who became the child’s godmother.

Sarah went on to have two more children with James, but then at just 37, she contracted tuberculosis and sadly died in August 1880.

Following her death, the Queen said: ‘My Black godchild was dreadfully upset & distressed. Her father has failed in business, which aggravated her poor mother’s illness. I shall give her an annuity.’ She then paid for Victoria to be educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, and stayed in touch throughout her life.

David Olusoga admits that when he first heard the tale of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, he struggled to believe it.

‘As I later discovered, some of her own descendants at once felt the same way,’ he explains. ‘They quite reasonably had presumed that her life story, which had been related to them by elderly relatives, must have been misremembered and exaggerated.

‘They imagined that over generations through multiple retellings, it had gradually become untethered from reality, transformed into a family legend. Only recently, have they and the rest of us come to understand that those suspicions were entirely unjustified.’

Meanwhile genealogist Emma Jolly, who has written about Sarah Forbes Bonetta, tells Metro.co.uk that her story needs to be retold now to counter the erasure of Black history.

‘Sarah has such an interesting story, and stories such as hers have been hidden – and we need to pull them out. We are a multicultural society and people need to see themselves represented in our history. There is a sense that there were no Black aristocrats or members of the upper classes in the past – and that’s not true.’

Dr Wanda Wyporska, chief executive of the Society of Genealogists, adds: ‘Black people are often told that our history can’t be found. But there is a growing awareness that actually we can find our stories in records.

‘There’s also an increasing feeling of Black empowerment and that we want to know our lives and our stories, because our history is being distorted.

‘If you don’t know your past and where you come from, it does have a bearing on you on your own situation and on your future. When we find out about ourselves and our families and what they’ve been through, then it does have a bearing on how we treat things in the present. So it’s a really important part of our identity.’

Black History Month

October marks Black History Month, which reflects on the achievements, cultures and contributions of Black people in the UK and across the globe, as well as educating others about the diverse history of those from African and Caribbean descent.

For more information about the events and celebrations that are taking place this year, visit the official Black History Month website.

Source: Read Full Article