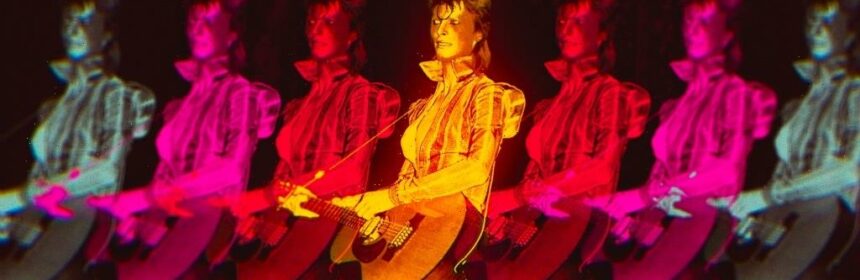

Seven Years, Thousands of Hours of David Bowie Footage and an Inspirational Train Ride Later, Brett Morgen Finally Realized His Moonage Daydream

September 15, 2022 1:30 pm

Bylines:By Pat Saperstein

Brett Morgen went through a lot to make “Moonage Daydream.” It takes certain amount of obsession to capture on film the essence of the life of David Bowie, the shapeshifting music visionary, artist and actor. For Morgen, known for his work exploring another singular artist with “Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck,” as well as “The Kid Stays in the Picture” and “Jane,” crafting the first authorized Bowie documentary was a nearly seven-year process. Until it was time to create the encompassing sound mix with help from Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti, he worked mostly alone, weathering both the pandemic and a serious heart attack.

“Moonage Daydream” is like no other music documentary audiences have seen before. With no talking heads or Bowie 101 facts, it’s geared towards super-fans and possibly the Bowie-curious, with sonically-enhanced remixes of more than 40 of his hits and lesser-played songs interlaced with never-before-seen images of his artwork, interviews with the singer and rare concert and movie footage. That alone would be a sensory overload and enough for a feature documentary, but Morgen also layers in clips of films Bowie had referenced at some point, from “Metropolis” and “A Clockwork Orange,” from “Freaks” and “La Dolce Vita,” creating a mind-bending two hour and 15-minute aural and visual experience.

So how did Morgen, who wrote and edited as well as directing, manage to wrestle all these sounds and all this imagery into shape? A train ride helped, plus a trip to the “David Bowie is” archival exhibit in Brooklyn and some intensive sleuthing for rare footage.

“Moonage Daydream” opens Friday in an exclusive IMAX presentation, expanding Sept. 23 to more theaters.

Morgen detailed some entry points into his creative process for Variety ahead of the film’s theatrical release.

Did you ever get to meet Bowie or tell him about your idea for a film?

I met David in 2007 to discuss a potential collaboration on a hybrid nonfiction project – not “Moonage Daydream,” something very different that was going to be more performance-based. That film that I pitched him imagined that David never evolved after Ziggy and that we would find him in present-day Berlin, and he has been playing the same songs for the past 40 years at a dive bar in the middle of the night to the last four people on Earth who are paying attention. It was a kind of wild presentation. It was going to require a lot of shooting and David was in semi-retirement at that point.

The man who became his executor called afterwards and said, you know, “David enjoyed the pitch but he’s not at a place where he can do this right now.”

So how did you come back around to doing a Bowie project?

Around 2015 I had done the two music films — “Crossfire Hurricane” (on the Rolling Stones) and “Montage of Heck,” and I sort of arrived at a point that I wanted to explore other areas – non-biographical non-fiction.

I wanted to create a kind of Immersive musical experience for IMAX and for a theatrical setting with these larger-than-life heritage acts. Most of us are familiar with the Wikipedia of their careers, and I just wanted to create a space for audiences to have an immersive and intimate experience with their favorite artist — a theme park ride, if you will, built around The Beatles and Bowie, Hendrix, whoever it might be.

So I started going down that path with several artists. Then in January 2016, Bowie passed.

After his estate agreed to the project, what was your next step?

At that point they provided me the with full access to explore the archives. The only dictate was David is not here to approve or authorize the project, so it can never be Bowie on Bowie. It will always need to be Brett Morgan on Bowie.

What was the scope of the archive?

It took the better part of two years to get that material digitized and collated, and then two more years for me to screen through it, six days a week in 12-hour days. I had possibly the two greatest years of my career going to work every day to watch and listen to David Bowie.

The problem was by the time I got to the end, I couldn’t remember what I had seen two years earlier. Normally what happens by screening things chronologically is a through line will emerge.

So what was the through line or the theme for you?

In Bowie’s case it was it was pretty transparent. He stated it repeatedly throughout his career: Chaos and fragmentation and transience. These are themes that he explored from his first recordings to his final recordings.

How did you decide to structure the material?

Usually the script pours out of me after I go through the materials and it’s a three to five day process. So I had in my schedule, you know, finish screening, write a script, start editing in a week. Usually, I write before I get to the edit room and I lay down the narrative that’s written notes tracking the through-line.

And very quickly it was revealed that I don’t know how to write an experience. I didn’t have a biographical narrative to lock onto.

And one week turned into two weeks, turned into four weeks, turned into six weeks and nothing is happening. It took eight months – going to work every day and coming home empty handed. I would start to write ideas — not about scenes, but ideas about Bowie on spirituality, Bowie on the creative process, Bowie on aging. Not really helping me advance the plot, but it was an exercise.

What was your breakthrough in terms of cracking the script?

I drove to work one day and I didn’t want to go into my office. It was like a coffin. Nothing was happening in there. So I I flew to Albuquerque on a whim and got on an Amtrak and I said I’m not coming home until I crack this.

One of the great lessons from Bowie is get out of your comfort zone. And one of the things that the film deals with head on is how Bowie liked to be in transit, to create and be a kind of cultural anthropologist.

So I got to Albuquerque, I got on a train, and the second the train started moving, the floodgates opened. By the moment I had arrived I had settled on the through line — transience. And so I then said let’s take three songs from each album that relate back to that theme, and curate a playlist that is the foundation of them, almost like a jukebox musical.

So when the train pulled into L.A., I had something to operate from.

In addition to the pandemic, you faced another huge hurdle during production.

The other major thing that had happened during this period was I had a heart attack and so I was in a coma for several days. I was 47. I have three teenage children. The way that I’ve been going about my life had led me to this, working nonstop and not exercising and not living a healthy life, not living life in balance. And so I needed to learn how to create more harmony and equilibrium in my life.

It seemed that David was providing me with a road map or a guide, a blueprint for how to lead a balanced and fulfilled life in an age of chaos and fragmentation. So while I had set out to make a theme park ride, I ended up seeing an opportunity for something more life-affirming.

How did you decide to integrate so many different film clips?

Bowie was a culture vulture. He was my cultural passport to the world, my introduction to William Burroughs. So I wanted the film to have almost no separation between Bowie’s own constructions and the work that inspired and influenced him. Any time he would reference something, I would write it down. When we started cutting, I had a huge folder of all of his reference points.

The clips that we see in the film, are they pretty much all based on something he’s mentioned? I didn’t realize that going into the screening.

Everything is based on something that he’s mentioned at some point. But here’s the thing — the same way you listen to Bowie songs and there’s no footnotes or Cliffs Notes. If you know what the reference is, that’s great. If you don’t know, that’s great too.

So how do you prepare the audience for the fact that they’re not going to receive a lot of biographical information?

If you’re opening with a quote about Nietzsche and about the search for meaning in life as the first thing, you’re probably not going to hear “the first time I heard my record on the radio.” It’s designed to be mysterious, designed to be enigmatic, designed to feel like there’s no compass.

It was amazing to see so much of Bowie’s own artwork, how did you get access to it?

I went to visit the David Bowie exhibit in Brooklyn. It felt like we were walking through the movie because the exhibit was equal measures David’s art and the art that influenced and inspired him.

But they didn’t have all of his paintings in the exhibit. The estate had transparencies that they provided us and some of it has been sold to collectors so we had to chase it down.

Was there anyone from his estate or elsewhere giving input during the process?

No, no.

This was really the the most difficult thing. So I have the heart attack. I was self producing. It’s just me, I had final cut, so the financiers weren’t involved in any creative discussions.

And I had no editor, there was no staff. And then the pandemic hit, and there was nobody in the building. So, other than my my wife, Debra Eisenstadt, who’s an incredible filmmaker who I could come home at night and throw ideas around to, I was completely isolated.

How did it work out to do it all yourself?

Through circumstances, some financial, some health-related because of the pandemic and because with my heart condition I can’t be around other people, it all worked. In a way I had to discover this on my own.

There probably was an easier path. I probably wouldn’t have been on the film for seven years. But I was kind of selfish and greedy and like, I wanted to be there. I wanted to make these mistakes, I wanted to figure this out.

It was a bit daunting, you know, it was like if I didn’t go to work, nothing was happening on the film. So the pressure to perform on a daily basis just so we can get through this was immense.

Did you always want to make it in in IMAX or when did that idea come about?

It was always there from conception. It was the idea of turning an IMAX space into a musical theme park and really turning on all of the speakers.

What were the most challenging parts to assemble?

I was limited to David’s voiceover, and I couldn’t get a phrase that I needed to get to the next scene. Right before, when he was making the turn to Iman, I didn’t have a transitional line. For each inch, it was like it was like trench warfare. But it was the most alive I’ve ever felt as an artist.

What was the most satisfying footage to track down?

Early on, I came across a VHS tape of a 1984 movie that David released called “Ricochet,” that was like a travelogue film. It was fairly dismissed at the time. It was David walking around Southeast Asia. I saw an awful VHS copy. There wasn’t anything on YouTube.

There was like nowhere to access this thing and I was like, oh my God, it’s the Holy Grail. It’s a stranger in a strange land. It’s the visual metaphor that I’ve been I need to anchor this film. And I called the estate and I said I need to get it because it wasn’t in our inventory list.

We looked for a year and a half. No one could find it, and then our archivist, Jessica Berman-Bogdan, stumbled across it by accident, filed under the wrong name. That to me was more valuable than any unseen, never-before-released stuff because I just knew how integral it was to the experience I wanted to present.

I was also able to see the complete Diamond Dogs show for which David had made a tape for himself. When David got to L.A. with the Diamond Dogs tour, he decided to abandon his sets and go back on the road as the Soul Tour with Luther Vandross and Mike Garson as the musical director. I had never seen or heard of any material from that and I came across two tapes of that tour.

How do you want viewers to watch it at home after the theatrical run?

Folks, whether you’re watching it on your phone, or you’re watching it in your living room, watch with headphones on.

What was it like to leave the editing room and finally go out into the world with the film?

It was mostly just me sitting here on a laptop. And then next thing you know, you’re at the Cannes Film Festival, in the Palais, with 2300 people. And it’s like, I can’t believe this happened, this is so weird. It’s like an arts and crafts project that’s now being presented in IMAX – around the world.

You mentioned thinking of doing a similar treatment for other music artists – who would be next on your wishlist?

One of the takeaways from my work with Bowie was the need to continue to challenge myself and move out of my comfort zone. I have decided to step away from archival filmmaking for a while and am developing something that’s more rooted in direct cinema.

(This interview has been edited and condensed.)

Brett Morgen went through a lot to make “Moonage Daydream.” It takes certain amount of obsession to capture on film the essence of the life of David Bowie, the shapeshifting music visionary, artist and actor. For Morgen, known for his work exploring another singular artist with “Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck,” as well as “The Kid Stays in the Picture” and “Jane,” crafting the first authorized Bowie documentary was a nearly seven-year process. Until it was time to create the encompassing sound mix with help from Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti, he worked alone much of the time, weathering both the pandemic and a serious heart attack.

“Moonage Daydream” is like no other music documentary audiences have seen before. With no talking heads or Bowie 101 facts, it’s geared towards super-fans and possibly the Bowie-curious, with sonically-enhanced remixes of more than 40 of his hits and lesser-played songs interlaced with never-before-seen images of his artwork, interviews with the singer and rare concert and movie footage. That alone would be a sensory overload and enough for a feature documentary, but Morgen also layers in clips of films Bowie had referenced at some point, from “Metropolis” and “A Clockwork Orange,” to “Freaks” and “La Dolce Vita,” creating a mind-bending two hour and 15-minute aural and visual experience.

So how did Morgen, who wrote and edited as well as directing, manage to wrestle all these sounds and all this imagery into shape? A train ride helped, plus a trip to the “David Bowie is” archival exhibit in Brooklyn and some intensive sleuthing for rare footage.

“Moonage Daydream” opens Friday in an exclusive IMAX presentation, expanding Sept. 23 to more theaters.

Morgen detailed some entry points into his creative process for Variety ahead of the film’s theatrical release.

Did you ever get to meet Bowie or tell him about your idea for a film?

I met David in 2007 to discuss a potential collaboration on a hybrid nonfiction project – not “Moonage Daydream,” something very different that was going to be more performance-based. That film that I pitched him imagined that David never evolved after Ziggy and that we would find him in present-day Berlin, and he has been playing the same songs for the past 40 years at a dive bar in the middle of the night to the last four people on Earth who are paying attention. It was a kind of wild presentation. It was going to require a lot of shooting and David was in semi-retirement at that point.

The man who became his executor called afterwards and said, you know, “David enjoyed the pitch but he’s not at a place where he can do this right now.”

So how did you come back around to doing a Bowie project?

Around 2015 I had done the two music films — “Crossfire Hurricane” (on the Rolling Stones) and “Montage of Heck,” and I sort of arrived at a point that I wanted to explore other areas – non-biographical non-fiction.

I wanted to create a kind of Immersive musical experience for IMAX and for a theatrical setting with these larger-than-life heritage acts. Most of us are familiar with the Wikipedia of their careers, and I just wanted to create a space for audiences to have an immersive and intimate experience with their favorite artist — a theme park ride, if you will, built around The Beatles and Bowie, Hendrix, whoever it might be.

So I started going down that path with several artists. Then in January 2016, Bowie passed.

After his estate agreed to the project, what was your next step?

At that point they provided me the with full access to explore the archives. The only dictate was David is not here to approve or authorize the project, so it can never be Bowie on Bowie. It will always need to be Brett Morgan on Bowie.

What was the scope of the archive?

It took the better part of two years to get that material digitized and collated, and then two more years for me to screen through it, six days a week in 12-hour days. I had possibly the two greatest years of my career going to work every day to watch and listen to David Bowie.

The problem was by the time I got to the end, I couldn’t remember what I had seen two years earlier. Normally what happens by screening things chronologically is a through line will emerge.

So what was the through line or the theme for you?

In Bowie’s case it was it was pretty transparent. He stated it repeatedly throughout his career: Chaos and fragmentation and transience. These are themes that he explored from his first recordings to his final recordings.

How did you decide to structure the material?

Usually the script pours out of me after I go through the materials and it’s a three to five day process. So I had in my schedule, you know, finish screening, write a script, start editing in a week. Usually, I write before I get to the edit room and I lay down the narrative that’s written notes tracking the through-line.

And very quickly it was revealed that I don’t know how to write an experience. I didn’t have a biographical narrative to lock onto.

And one week turned into two weeks, turned into four weeks, turned into six weeks and nothing is happening. It took eight months – going to work every day and coming home empty handed. I would start to write ideas — not about scenes, but ideas about Bowie on spirituality, Bowie on the creative process, Bowie on aging. Not really helping me advance the plot, but it was an exercise.

What was your breakthrough in terms of cracking the script?

I drove to work one day and I didn’t want to go into my office. It was like a coffin. Nothing was happening in there. So I I flew to Albuquerque on a whim and got on an Amtrak and I said I’m not coming home until I crack this.

One of the great lessons from Bowie is get out of your comfort zone. And one of the things that the film deals with head on is how Bowie liked to be in transit, to create and be a kind of cultural anthropologist.

So I got to Albuquerque, I got on a train, and the second the train started moving, the floodgates opened. By the moment I had arrived I had settled on the through line — transience. And so I then said let’s take three songs from each album that relate back to that theme, and curate a playlist that is the foundation of them, almost like a jukebox musical.

So when the train pulled into L.A., I had something to operate from.

In addition to the pandemic, you faced another huge hurdle during production.

The other major thing that had happened during this period was I had a heart attack and so I was in a coma for several days. I was 47. I have three teenage children. The way that I’ve been going about my life had led me to this, working nonstop and not exercising and not living a healthy life, not living life in balance. And so I needed to learn how to create more harmony and equilibrium in my life.

It seemed that David was providing me with a road map or a guide, a blueprint for how to lead a balanced and fulfilled life in an age of chaos and fragmentation. So while I had set out to make a theme park ride, I ended up seeing an opportunity for something more life-affirming.

How did you decide to integrate so many different film clips?

Bowie was a culture vulture. He was my cultural passport to the world, my introduction to William Burroughs. So I wanted the film to have almost no separation between Bowie’s own constructions and the work that inspired and influenced him. Any time he would reference something, I would write it down. When we started cutting, I had a huge folder of all of his reference points.

The clips that we see in the film, are they pretty much all based on something he’s mentioned? I didn’t realize that going into the screening.

Everything is based on something that he’s mentioned at some point. But here’s the thing — the same way you listen to Bowie songs and there’s no footnotes or Cliffs Notes. If you know what the reference is, that’s great. If you don’t know, that’s great too.

So how do you prepare the audience for the fact that they’re not going to receive a lot of biographical information?

If you’re opening with a quote about Nietzsche and about the search for meaning in life as the first thing, you’re probably not going to hear “the first time I heard my record on the radio.” It’s designed to be mysterious, designed to be enigmatic, designed to feel like there’s no compass.

It was amazing to see so much of Bowie’s own artwork, how did you get access to it?

I went to visit the David Bowie exhibit in Brooklyn. It felt like we were walking through the movie because the exhibit was equal measures David’s art and the art that influenced and inspired him.

But they didn’t have all of his paintings in the exhibit. The estate had transparencies that they provided us and some of it has been sold to collectors so we had to chase it down.

Was there anyone from his estate or elsewhere giving input during the process?

No, no.

This was really the the most difficult thing. So I have the heart attack. I was self producing. It’s just me, I had final cut, so the financiers weren’t involved in any creative discussions.

And I had no editor, there was no staff. And then the pandemic hit, and there was nobody in the building. So, other than my my wife, Debra Eisenstadt, who’s an incredible filmmaker who I could come home at night and throw ideas around to, I was completely isolated.

How did it work out to do it all yourself?

Through circumstances, some financial, some health-related because of the pandemic and because with my heart condition I can’t be around other people, it all worked. In a way I had to discover this on my own.

I I mean, I didn’t have to. There probably was an easier path. I probably wouldn’t have been on the film for seven years. But I was kind of selfish and greedy and like, I wanted to be there. I wanted to make these mistakes, I wanted to figure this out.

It was a bit daunting, you know, it was like if I didn’t go to work, nothing was happening on the film. So the pressure to perform on a daily basis just so we can get through this was immense.

Did you always want to make it in in IMAX or when did that idea come about?

It was always there from conception. It was the idea of turning an IMAX space into a musical theme park and really turning on all of the speakers.

What were the most challenging parts to assemble?

I was limited to David’s voiceover, and I couldn’t get a phrase that I needed to get to the next scene. Right before, when he was making the turn to Iman, I didn’t have a transitional line. For each inch, it was like it was like trench warfare. But it was the most alive I’ve ever felt as an artist.

What was the most satisfying footage to track down?

Early on, I came across a VHS tape of a 1984 movie that David released called “Ricochet,” that was like a travelogue film. It was fairly dismissed at the time. It was David walking around Southeast Asia. I saw an awful VHS copy. There wasn’t anything on YouTube.

There was like nowhere to access this thing and I was like, oh my God, it’s the Holy Grail. It’s a stranger in a strange land. It’s the visual metaphor that I’ve been I need to anchor this film. And I called the estate and I said I need to get it because it wasn’t in our inventory list.

We looked for a year and a half. No one could find it, and then our archivist, Jessica Berman-Bogdan, stumbled across it by accident, filed under the wrong name. That to me was more valuable than any unseen, never-before-released stuff because I just knew how integral it was to the experience I wanted to present.

I was also able to see the complete Diamond Dogs show for which David had made a tape for himself. When David got to L.A. with the Diamond Dogs tour, he decided to abandon his sets and go back on the road as the Soul Tour with Luther Vandross and Mike Garson as the musical director. I had never seen or heard of any material from that and I came across two tapes of that tour.

How do you want viewers to watch it at home after the theatrical run?

Folks, whether you’re watching it on your phone, or you’re watching it in your living room, watch with headphones on.

What was it like to leave the editing room and finally go out into the world with the film?

It was mostly just me sitting here on a laptop. And then next thing you know, you’re at the Cannes Film Festival, in the Palais, with 2300 people. And it’s like, I can’t believe this happened, this is so weird. It’s like an arts and crafts project that’s now being presented in IMAX – around the world.

You mentioned thinking of doing a similar treatment for other music artists – who would be next on your wishlist?

One of the takeaways from my work with Bowie was the need to continue to challenge myself and move out of my comfort zone. I have decided to step away from archival filmmaking for a while and am developing something that’s more rooted in direct cinema.

(This interview has been edited and condensed.)

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article