The name’s Orlick: Why Stanley Tucci nails the spy who loves nuance

By Michael Idato

Credit:New York Times

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Much like the character he plays in the new Amazon spy drama Citadel, Stanley Tucci is a man for the modern era. As an actor, he has escaped pigeonholing by starring in everything from Transformers and The Hunger Games to understated dramas such as Supernova and The Daytrippers. He has also shown a dab hand as a writer (his memoir Taste was published to strong reviews last year) and as host of his own culinary travel series, Searching for Italy.

In Citadel, he plays master spy agent Bernard Orlick, who is charming, somewhat suave and perhaps, within the genre, uniquely metrosexual. Far from inheriting the post-sexploitation misogyny that is synonymous with the world of James Bond, Orlick is the sort of spy who has one hand on the trigger, and the HR department on speed dial. By design he’s intended to appeal to everyone. And he has a very contemporary talent for nuance.

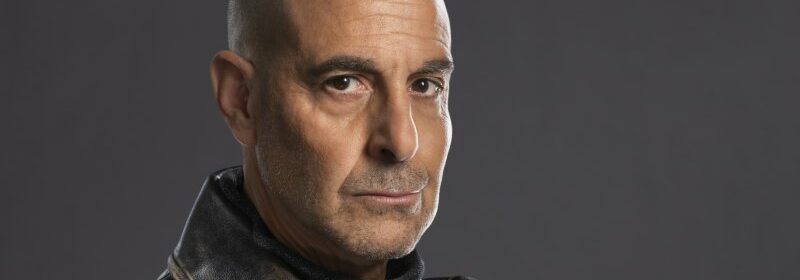

Stanley Tucci in Citadel: “The ambiguity of the characters is what makes them interesting.″Credit:Amazon

What is self-evident from the start is that Orlick is good, and that his rival, the sinister Dahlia Archer (Lesley Manville), is bad. But unlike in the Bond universe, those alignments are not so easy to discern.

“You can’t trust anybody,” Tucci says, smiling. “I mean, that’s sort of one of the points of the show, is that you don’t know who to trust in any given moment. I think, in the end, the ambiguity of the characters is what makes them interesting.”

The series comes as Tucci has reshaped much of his life. In the past decade, he married British literary agent Felicity Blunt, moved from the east coast of the United States to London, and evolved from a character actor, known for roles in Prizzi’s Honor (1985) and The Lovely Bones (2009), to a man for all seasons. He even brought charm and intrigue to his role as a former criminology professor on death row for killing his wife in last year’s Inside Man.

As the producer and presenter of Searching for Italy, he embarked on both an exploration of that country’s culinary and cultural notes and his own identity as an Italian-American. Its greatest challenge: managing the expectation that he can play himself when the cameras are rolling, rather than hide, as many actors do, behind the safety blanket of Ibsen, Chekhov or Strindberg.

Stanley Tucci shares a meal in Searching for Italy.

“It was uncomfortable at the beginning,” Tucci says, of learning to be himself in front of the camera. “I didn’t really know how to do it. You think you know how to do it, and then you realise you don’t know how to do it. Now, I’m much more comfortable with it. Now, I know how to do it.”

Part of the appeal in taking on the role of Orlick was the way Citadel updates our ideas about role models. We are not long into the series before bullets are flying and high-tech gadgetry is being used to bail the show’s protagonists, Mason Kane (Richard Madden), Nadia Sinh (Priyanka Chopra Jonas) and Orlick, out of genre-stretching sticky situations.

Such scenes feed on the fantastical dreams of our shared cultural childhoods, where our career aspirations began with astronaut, archaeologist or spy, and our role models were – depending on your age – Ellen Ripley, Emma Peel, Indiana Jones, James Bond or anyone in between.

“Without question, I loved those James Bond movies when I was a kid,” Tucci says. “I think it’s fascinating. But I think, also, times are changing, so little girls have that same fantasy and that same interest, and that’s really good. Look at what Priyanka Chopra Jonas does in this series. It’s really exciting.”

As projects go, Citadel is not unambitious. Steered creatively by screenwriter David Weil and blockbuster filmmakers Anthony and Joe Russo, it has a price tag of $US300 million ($4.53 million) for its six one-hour episodes, and ambitious plans for two spin-off series, one set in India and the other in Italy, both expanding the show’s international espionage storyline.

In the universe of Citadel, Tucci’s Orlick is a sort of combo of the James Bond universe’s M and Q, both commander-in-chief and technical gizmo consultant. Here is your mission, and here is your shoe telephone. Or your exploding earrings. Or your wristwatch that is, in fact, an aeroplane.

Stanley Tucci as Bernard Orlick in Citadel.Credit:Amazon Prime

“He is what you see, but then it’s enhanced by rewriting, by some improvisation, and then of course, as you’re interacting with the other actors, that’s going to change your performance and delivery and maybe even what you say,” Tucci says of the role.

“A lot of times I will have a tendency to cut dialogue because I think a lot of things are overwritten, and we can tell so much with our faces, or our bodies, or whatever, or one word. So it’s something that is always in flux.”

The expensive fabric of the Citadel universe has been stitched together by the Russo brothers, best known as the architects of the final chapters of the Avengers saga, tying together the strands of Marvel’s various cinematic strings for the two-part ensemble finish, Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019).

But unlike most of their contemporaries, who sprang from the school of Star Wars storytelling – and now largely deliver father-son stories as a result – the Russos came from a childhood spent gaming, notably the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons.

That game’s specifics – the principle of sandbox storytelling, coupled with a groupthink “party” approach to play – perhaps makes them uniquely skilled in ensemble world-building. In Citadel, they quickly establish a near-future world where rival intelligence agencies have, at various times, attempted to knock one another out. At present, that score would be Manticore 1, Citadel 0.

“They have an ability to see imaginary worlds and create imaginary worlds better than probably anybody I know, but they also have an understanding of the nuances of human behaviour,” Tucci says. “And the combination of those two things is what has made them so successful.”

What makes the Citadel universe so specifically fascinating is that unlike, say, the James Bond universe, where the ethical axis is reasonably clear and you can easily see where everyone sits on it – that is, James Bond is a goodie, and, say, Auric Goldfinger and Francisco Scaramanga are baddies – in Citadel those alignments are less easy to discern.

While Orlick is good, and Dahlia Archer is bad, there is an unease around those presumptions, and an expectation that in line with most modern streaming dramas, the Russos are just one episode ahead, with their hands on the rug, waiting to yank it out from under us.

“A character that isn’t ambiguous, really, after a while, you already anticipate what that person is going to do, how they’re going to react to any given situation, and the ambiguity makes it much more interesting,” Tucci says.

“I think that Bernard is somebody who does what he has to do to achieve the results that he wants. The main result that he wants is for Citadel to be successful, for Citadel to be the force of good in the world, as he says. And if sacrifices have to be made, including his own life, that’s something that will happen.”

While Citadel is obviously fictional, Tucci believes the appeal lies in its pseudo-political themes, a dark reflection of the increasingly erratic real world. “There’s an intelligence to it, and you see from the very beginning, even in the trailer, the description of these covert entities that are co-ordinating nefarious or good things in the world that people don’t know about,” he says.

“It’s innately political. And it is, without question, commenting on the truthfulness of our government and its infrastructure. I like that, because we’re sort of walking on quicksand these days. We don’t know who to trust. Things were a lot clearer many years ago. Not that everybody was trustworthy, just that it was clearer.

“We have so much information [today]; some of it is really important because we’re learning things that we’ve never learnt before about our governments, most of which aren’t really very good, and then there’s all that disinformation, all those false truths,” Tucci says. “To have all of those things at once in our society, we’ve never had that before. Usually, we find out years later. Now, we’re finding stuff out immediately.”

A man for all seasons: Stanley Tucci in, from top left, Hunger Games, Inside Man, Supernova, Worth and Julie & Julia.Credit:

The decision by the Russo brothers to cast Tucci in Citadel leverages the very specific qualities of the real man. His sex appeal, which is undeniable. His style and sophistication, evident in both his social media life and his memoir. And his presence, attributable perhaps to his New York origins. Without all of those things, Bernard Orlick could not exist.

Tucci’s self-assurance is evident when you meet him. And he insists that the real-world journey does not fundamentally change him as an actor, even if it changes his perspective of the world in which he acts. “I don’t know that every role is an exploration of who you are,” he says. “It’s a piece of who you are, but it’s not [everything] … if every role were an exploration of who you are, you could do three roles and then you’d drop dead.

“It’s a job, you go in, you know your lines, you hit your marks, you make it as truthful as possible, and then you take off your costume and you go home. Otherwise, it’s not fun. It wouldn’t be fun, and it wouldn’t be fun for you, and it wouldn’t be fun for anybody.”

But the transformative effect of his Italian journey, Tucci says, has been profound. “It has changed my life significantly because I am just me. That’s never happened before. I’ve never done that before, with the exception of interviews or something. Maybe one of the reasons we’re actors is because we’re not comfortable with ourselves, but I suppose this has made me a little more comfortable with myself.”

Maybe he is, maybe he’s not. In a 2021 profile published by The New Yorker, writer Helen Rosner described him as the “master of the charismatic smolder”. He’s a little startled when I point it out. It’s a magnificent descriptor, I tell him. But are such observations as helpful as they seem? “They can make you a little self-conscious,” he says. “But it’s a very nice compliment.”

Citadel is streaming on Amazon.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article