The self-deprecating masterpiece that opens Colm Toibin’s new book

Colm Toibin is the opposite of the “reclusive writer” (think J.D. Salinger or Thomas Pynchon). If you catch any of his many interviews or media appearances, you’ll experience a warm and gregarious personality, speaking at breakneck speed, full of gossip, mischief, sparkle.

Yet when he stands up to read his work, fiction or non-fiction, the pace slows dramatically, his voice become rhythmic, deliberate, mellifluous, lingering over a cadence or a detail. His prose style, if not quite austere, tends towards the restrained, the scrupulous, the exact and the precise.

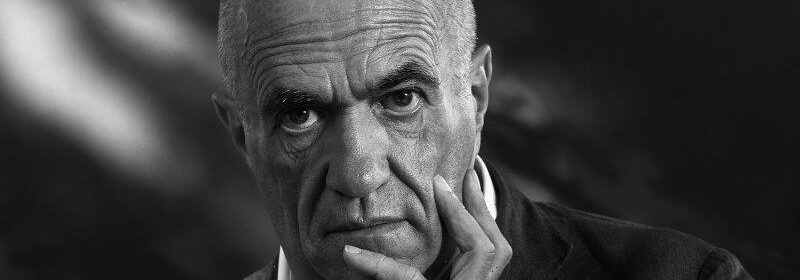

At his best Colm Toibin is a great observer of the world and appreciator of his fellow artists.Credit:New York Times

He is an extremely funny man but has, curiously enough, never written a funny book, though the first in this collection of essays, Cancer: My Part in its Downfall is a masterpiece of mordant self-deprecation.

Australian readers will know Toibin mainly as the acclaimed novelist, short-story writer and, perhaps, as an essayist (eight of the 11 essays here first appeared in The London Review of Books). However, when I was growing up in Dublin in the 1980s and early ’90s, he was best known as a newspaper columnist and magazine editor.

A Guest at the Feast by Colm Toibin.

This journalistic background, touched on in several pieces here, is the key to understanding him as a writer. He’s concerned with facts, rather than symbols, suspicious of the portentous or mystifying, whether of religious authority or Irish nationalism. His forensic prose, if appealing artistically, also has the dispassionate and neutral quality of the reporter.

This is one reason why, while he often writes about himself, Toibin is not particularly self-revelatory. The title essay in this collection, the longest piece, is the most autobiographical, dwelling a great deal on his childhood in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, but ranging also to his early adulthood in Dublin. Its division into sections gives it an elliptical quality, pivoting between memory and social history, but also fastening on to descriptive details.

It’s hardly a surprise that a gay man born in Ireland in 1955 would be well-equipped at deflection and self-concealment. Yet it becomes in its way a whole aesthetic of surfaces.

Reflecting on the eroding cliffs on the coast of Wexford that found its way into several of his novels and short stories, he writes, “I suppose this is an interesting image of time and a metaphor for what time does. But I am more interested in the exact thing itself – the actual detail of this landscape that I have known for so long falling, dissolving, being washed away, not being there anymore.”

Things don’t resonate or symbolise, they simply happen. This is part of Toibin’s resolutely secular way of seeing, a secularism that emerges alongside an Ireland that has sloughed off an older belief system, one that is not just Catholic but still tied into pagan energies – the knocking at the door that heralds an imminent death, which his mother heard in 1960 for the last time.

Toibin campaigned for modernity, secularism, the opening up of Ireland to the outside world. The essay here on the Ferns Report into clerical sex abuse in the diocese of Ferns in Wexford searingly shows how necessary the challenge was to traditional religious authority.

Yet Toibin does not quite know what to do with the victors’ spoils. It’s striking how little he has to say about the problems of contemporary Ireland, the state that recently garlanded him as its Laureate of Fiction. His fictional imagination goes back to earlier decades in novels such as Brooklyn or Nora Webster.

These essays also go back and repeatedly veer towards religious or clerical matters. “One of the purposes of literature, as Joyce made clear, is to put religion in its place.” But Toibin is drawn to religion, I think, for reasons different from Joyce – whose mind was saturated with Catholic theology. Rather, Toibin has the reporter’s nose for getting to the real story, uncovering what lies beneath the “Bergoglio Smile” of Pope Francis or the red Prada shoes of Pope Benedict (Among the Flutterers).

That trawl to capture things makes the writing assiduous and, for me, the tendency to quote can be too thick. However, at his best Toibin is a great observer of the world and appreciator of his fellow artists. Thanks to this book (and Spotify), I have now discovered Frederick May’s string quartet, “one of the most exquisite contributions to Irish beauty that has ever been made”.

An essay here on Marilynne Robinson, taking in religious themes in a range of writers from Larkin and Eliot to Henry James, shows that the friction of faith against Toibin’s unbelief brings out what he does best as a critic: noticing things, even in their momentary transience, and appreciating the craft of writing.

A late piece here on the great Irish novelist John McGahern quotes, with savour, even exhilaration, a comment that McGahern made to Toibin over a whiskey, after the former’s terminal cancer diagnosis: “You would want to be an awful fool not to know that we only bloom once.”

A Guest at the Feast by Colm Toibin is published by Picador, $34.99.

Ronan McDonald holds the Gerry Higgins Chair of Irish Studies at the University of Melbourne.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article