‘When It Melts’ Review: Childhood Trauma is Inescapable in a Well-Crafted But Bottomlessly Bleak Debut

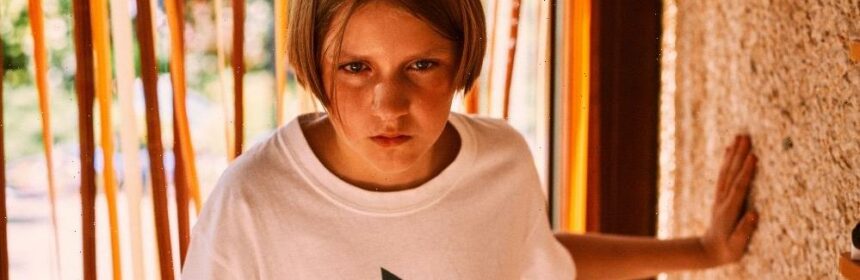

A couple of times over in “When It Melts,” the directorial debut of Belgian actor Veerle Baetens, Eva, played as a morose, withdrawn adult by Charlotte De Bruyne, looks at a photograph of herself as a 13-year-old. In the picture, child-Eva (Sundance prizewinner Rosa Marchant) is grinning a lopsided, optimistic tomboy grin, unaware of the violent end of innocence lying in wait for her. The space between these two Evas — a vast gulf not just temporal but scarringly psychological — is territory painstakingly mapped out by Baetens, whose grip on the tone of gathering dread is sure, until it becomes suffocating. As the story pivots back and forth between its two timelines, as though hoping one will hold the key to the other’s release, it grows oppressive, as hard to witness as a cornered bird battering itself helplessly against one window, then the next.

Eva is a shy photographer’s assistant, in the habit of rebuffing her boss’s gently flirtatious invitations for an after-work drink, instead going straight home to the apartment she shares with her younger sister Tess (Femke Van der Steen) and a pet turtle. But her cloistered life is disrupted when Tess moves out –– with the help of their parents, from whom Eva is pointedly estranged. Alone one evening, Eva happens on a Facebook invite to a celebration in her childhood hometown. She clicks “will attend,” and sets about preparing for the trip: packing up the turtle, loading up the car. Oh, and collecting the massive block of ice we saw her make in her deep freeze during the film’s grim prologue, and storing it in a cooler box for the journey.

Meanwhile, unfolding in parallel but in sunnier hues, tween Eva is enjoying bike rides and backyard-pool dips with her childhood besties, Tim (Anthony Vyt) and Laurens (Matthijs Meertens). (Frederic Van Zandyke’s atmospheric photography is a little over-literal in contrasting a vibrant, nostalgic then with a desaturated, cool-toned now.) She nurses a little crush on ringleader Tim, but the two boys are oblivious to her as a girl, and react with scorn when she tries hesitantly to stop them from luring neighborhood kids they fancy into playing stripping games.

Terrified of losing her place in the threesome, on the outs with her drunken mother and distant dad, and embarrassed by her perceived plainness alongside a glamorous blonde newcomer who immediately catches Tim’s eye, Eva pivots to becoming the boys’ procurer, luring local girls into ever more manipulative versions of the game. She even supplies the riddle that forms its centerpiece: the one about the dead man found hanging in a locked unfurnished room, with nothing but a puddle of water under his feet.

The flashback sections of the film are the more successful, in part because of Marchant’s excellent, truculent turn as young Eva, and the painfully accurate observation of how easily the acute desire to fit in with one’s peers can become a horribly self-destructive force during adolescence. But it’s also because it’s only here that there is any moderation in the film’s overridingly dour and doom-laden tone, and even so, these brief moments of carefree happiness are always undercut by Bjorn Eriksson’s sinister, thriller-inflected score.

Even the warmth of Eva’s connection with Laurens’ mom (Femke Heijens) — the jolly local butcher who calls the trio “The Three Musketeers,” and lavishes on Eva the comfy maternal affection she doesn’t get at home — seems highlighted mainly to make her betrayal hurt all the more, when she’s forced to choose between doing right by the little girl or protecting her son from the consequences of his actions. For a film ostensibly revolving around misogynistic, male-on-female violence, “When It Melts” is especially scathing in exposing the lie of female solidarity when self-interest — be it love for a son, revenge for a slight, or simple peer advancement — is on the line.

There can be a rewarding kind of connection when stories of melancholy, heartbreak or devastation are shared — something that, as an actor, and particularly as the star of Felix Van Groeningen’s eviscerating “The Broken Circle Breakdown,” Baetens knows a thing or two about. And as a director, she seems interested in exploring the similarly distressing landscapes of loss and hurt provided by Lize Spit’s Flemish literary phenomenon “Het Smelt,” which Baetens adapts along with co-writer Maarten Loix.

But despite the sincere intentions, strong performances and skillful craft on show in “When it Melts,” it never quite connects. Perhaps that’s down to the rather maudlin characterization of Eva as a woman defined wholly by her victimhood, and by a trauma that, dispiritingly and contrary to popular therapeutic belief, does not lessen through confrontation. Perhaps it’s the unwavering mood of impending disaster. Or perhaps it’s the pitiless conclusion, which is both too narratively neat to be credible as slice-of-life realism and too much of a downer to deliver any much-needed thriller-like catharsis. Whatever the reason, Eva’s plight, and Baetens’ film, is harrowing rather than moving. Perhaps that’s appropriate, given that this is a story in which ice melts faster than hearts, and faster still than the frosty wall of silence built around young boys who do terrible things, no matter the cost to the young girls they do them to.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article