Memories of My Father Review: An Unapologetically Sentimental Biopic About a Bold Doctor in Medellín

A bracingly affectionate biopic that compels despite (and because) of its unapologetic sentimentality, Fernando Trueba’s “Memories of My Father” pays loving tribute to someone who took comfort in the knowledge that he would be forgotten. His name was Héctor Abad Gómez, a medical doctor and university professor in Medellín who founded the Colombian National School of Public Health. He cared so deeply about the public health of his country’s poorest souls — to the great agitation of right-wing paramilitary groups — that it was as if he’d taken the Hippocratic Oath as his own personal eucharist.

Adapted from a popular memoir by the late doctor’s son, Trueba’s film overcomes its ham-fisted clumsiness because it goes a step beyond hagiography. It’s a story filtered through the eyes of a grieving son in complete awe of his father, one told with enough warmth and detail that it could be easy to forget its memories don’t belong to the filmmaker himself.

That isn’t much of a surprise, as warmth and detail have been Trueba’s most consistent strengths since the Spanish filmmaker burst onto the world stage with hits like “Opera prima” (1980) and “Belle Époque” (1992). If true greatness eluded him then — as it continues to elude him now — that has never felt like Trueba’s primary concern. Much like the subject of his latest feature, the director has always seemed motivated by life and vitality at the expense of everything else. Trueba knows what Héctor Abad Faciolince sees when he thinks of his father. The filmmaker embraces that venerative spirit with a semi-religious zeal that allows “Memories of My Father” to survive its molasses-thick melodrama, outrun its naïve vision of political violence, shake free from the “Roma” comparisons that have dogged it since its 2020 Cannes premiere, and find a small measure of the beauty that Gómez sought to the end.

In “Memories of My Father,” the “present” (actually 1983) is shot in black-and-white, and the “past” (a broad swath of time across the early ‘70s) is rendered with deep smudges of digital color that capture the slippery magic of a childhood idyll. Played by Juan Pablo Urrego as a college-age man, Héctor Abad Faciolince is introduced watching Oliver Stone’s “Scarface” on a date in Italy, and something about the movie’s violence summons him back home to Medellín, where his family has gathered for their patriarch’s retirement ceremony. It’s not a happy occasion. Gómez isn’t stepping down so much as being forced out of the university for political convictions — namely, that he has some.

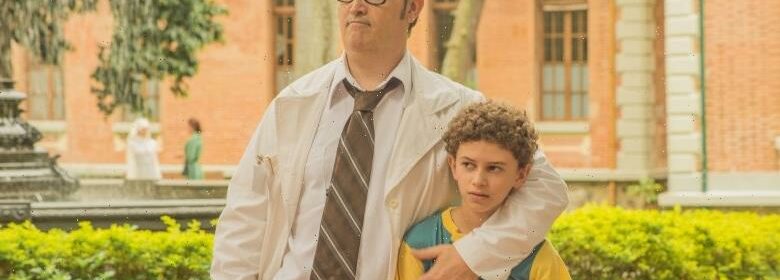

We don’t get a good look at Gómez during the ceremony. When the movie finally introduces him in flashback, we immediately understand why: As embodied by the great Spanish actor Javier Cámara (who’s as unforgettable here as he was as the virginal obsessive in Almodóvar’s “Talk to Her”), it’s impossible to imagine Gómez surrendering to the dictates of anything he doesn’t believe in.

A fast-talking egghead whose closest pal is played by Whit Stillman, Gómez still acts like a rebellious student even as he strides through the world with the kind of confidence that sons futilely aspire to match in their fathers. He combines the moral stature of Atticus Finch with the socialist affinities of Bernie Sanders. He also disavows any formal political leanings, insisting that our hearts are on the left side of our bodies and our bile ducts on the right. Gómez forces his kids to learn from their mistakes and face up to their deficiencies — at one point dragging his only son to a Jewish neighbor’s house so that he can apologize for throwing stones at it — but young Hector reveres his father for that, to the extent that he comforts himself by smelling Gómez’s pillow after the professor has to find work away from home.

Home is an especially meaningful place to Hector and his four sisters; it’s a buzzing nexus of relatives, medicine (Gómez forces his kids to be guinea pigs for a typhoid vaccine), religion (a disapproving nun pops up like she’s part of the furniture), female secrecy (many of Hector’s childhood memories revolve around being shooed away from girls-only conversations), and the affection that Gómez lists as one of a human being’s five greatest needs. Most of all, the family’s upper-middle-class home is a venue for music, specifically the dreamy acoustic Beatles and Rolling Stones covers that Hector’s sister Marta performs for everyone in the living room.

These “Leave it to Beaver”-worthy scenes of the nuclear family are the beating heart of Trueba’s film and strain to justify the nostalgic exuberance that blooms across many of its rose-colored flashbacks. Shots of Hector’s family all cozy in the same bed feel mawkish in a way that wouldn’t seem to belong in a movie about a hard-nosed intellectual, but Gómez insists that violence is born from cowardice, and “Memories of My Father” refuses to lack the courage to love — or to refrain from depicting Marta’s premature demise with a fuzzy home video montage of her slipping away to the sound of her favorite song. It’s an egregiously saccharine choice, and yet one that can’t help but jive with the spirit of a movie so determined to preserve the memories of pure-hearted people who died senseless deaths.

From the moment that Gómez conflates his socialist tendencies with the principles of Christian doctrine, Trueba’s film is likewise determined to render love with an ecclesiastic purity that supersedes all other truths. That focus can’t help but imbalance “Memories of My Father” towards its flashbacks and deprive this leisurely-paced story of the urgency that its more harrowing “present” sections demand.

Adult Hector’s violent confrontations with his own privilege and personal responsibility are watered down by his increasingly muddled view of his father, even if there’s an unfortunate honesty to how Gómez becomes defined by the same political rhetoric that he’s fighting against. The warmth that once held Trueba’s film together cools into something that doesn’t reward its sentimentality in the same way, and Gómez’s story ends with the whimper of a death foretold. And yet “Memories of My Father” is evocative enough to eke by on its own terms. Gómez was always certain that he would be forgotten; Trueba respects the comfort he found in that fact while also whispering sweetly, lovingly, “Not yet.”

Grade: B-

Cohen Media Group will release “Memories of My Father” in theaters on Wednesday, November 16. Quad Cinema’s “The Ages of Trueba” retrospective runs November 14–17.

Source: Read Full Article