From the Archives, 1983: A slice of history that Melbourne forgot

First published in The Age on March 15, 1983

A slice of history the world forgot

A beautiful piece of history has come up from the basement of the State Library in Melbourne. It is so rare that nobody quite knows what to do with it.

You have heard of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts life in 11th century France? Well, the thing that has come up from the basement depicts life in Melbourne in 1841.

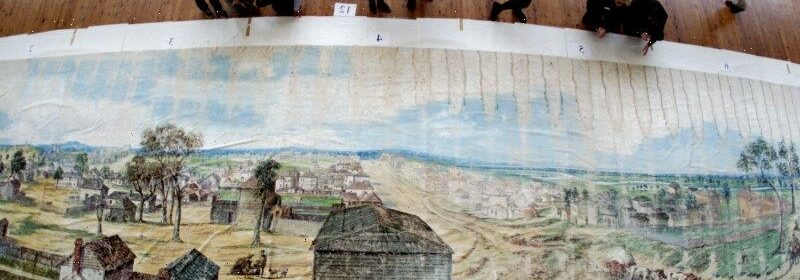

A 30-metre cyclorama painting showing a 360 degree view of Melbourne in the 1840s, which was unrolled in 2000 at the Melbourne Exhibition Buildings.Credit:Craig Sillitoe

It is a whopper — a canvas that stretches for nearly 33 metres and is five metres deep. If you tried laying it across the Bourke Street Mall, it would not fit. You would be left with about two metres curling up the display windows of Buckley’s.

The name for such a work is cyclorama, which was once very familiar to our grandparents and great-grandparents. At the end of last century, a cyclorama was the equivalent in entertainment to the movies.

It was a panorama of an event or a scene that was painted in such a way that when you joined the two ends and made a circle, you got a view covering 360 degrees. Some cycloramas were enormous — up to 122 metres long (or round).

Let your mind wander back to Melbourne in 1841, six years after its foundation. One of the best-known men in the town was Samuel Jackson, a builder and architect of many pioneer banks and churches, including St Francis’s and Scots.

One day in July of that year (so the story goes) Samuel Jackson sat in, or on, a revolving barrel on the half-finished walls of Scots Church, at the corner of Russell and Collins streets, and in this mad position he sketched a 360-degree view of Melbourne in pencil and wash.

It was not a big thing by later standards — about five metres long by 15 centimetres deep. The Victorian Government acquired it in 1888, and it is kept now in the research room at the La Trobe Library.

Soon afterwards, the Government wanted the sketch photo-graphed and enlarged. The task fell in the end to John Hennings, the hero of this story, who did the enlargement by paint, not photography. Hennings painted what we now know as the cyclorama from the basement.

Hennings was an important man in the Melbourne art circles of his day. He was a scenic designer who came to Australia from Germany in 1855, and he became associated almost at once with Melbourne’s Theatre Royal, of which he was a director. His friends were the artistic and the cultivated.

How long he took to paint the cyclorama we do not know. We do know, however, that it was hung in the aquarium annexe of the Exhibition Building on 23 September 1892, and it stayed there at least until the 1920s, probably longer. Then the world seemed to forget it.

Enter Mimi Colligan, a research assistant doing a PhD thesis with the department of history, Monash University. The thesis, still unfinished, is called ‘Popular Entertainment in Melbourne 1857-1920 — Images of History’. It starts with the waxworks and ends with the movies.

Ms Colligan, of East Brighton, had been working away for two years before she learned to her amazement that the cyclorama still existed. From what I gather, this discovery came out of a casual conversation with a member of the library staff. You know the sort of thing — “By the way, I believe you are interested in a cyclorama?” —some sort of conversation like that.

The cyclorama was brought up from the basement and unrolled on the floor as far as it would go (33 metres takes up a lot of space). One can easily imagine what such a find can mean to an historian. “Tears came to my eyes when I saw it,” Ms Colligan says.

The other day, the State Librarian, Mr Warren Horton, and the La Trobe librarian, Dianne Reilly, authorised the staff to unroll it for me. What a fascinating thing it is. Rich in colour and enthralling in its detail.

Water has damaged it in many places, but the charm has survived. What a solid look Melbourne had, even before the opulence of the gold rush. What neatness and order in the houses and streets. This was a town of merchants and capital.

The squat little houses are of wood, stone and brick, and they have shingle roofs. Already they are becoming more than one storey high.

Washing hangs to dry on a block of land where the solid folk later built the town hall. Everybody’s lavatory is shown, down by the back fences. Bullocks plod along with a dray, and beside them leans a man on a fence. I think he must be the driver. He seems to be having his smoko.

Chooks fuss around a backyard, and a cheeky rooster balances on the fence. It could be early morning, because not many people are astir. A horseman gallops along with a basket. Is he going to trade his produce?

Macedon and the Dandenongs are in the background, way out there beyond the flagpole and the cemetery on flagstaff Hill. A pretty paddock is in the east. Perhaps it is the one that became the MCG. And look — there’s La Trobe’s Cottage, on its old site at Jolimont.

And see how the cabbages are growing in this vegetable garden. What healthy cabbages.

Comparing the Jackson sketch and the Hennings cyclorama, one quickly sees that Hennings made some changes. The original scene (the sketch) is full of bustle. All sorts of people are doing all sorts of things.

The cyclorama, on the other hand, in the words of Ms Colligan, is more theatrical and romantic. “Hennings painted in bright colours and gave more emphasis to topographical features such as the distant hills and the meeting of the Yarra and the Salt Water Creek,” she says.

She also points to an interesting contrast in the Aborigines. Jackson’s depiction of them (1841) seems to give them a more noble appearance than that of Hennings.

This is a subjective judgment, but worth thinking about. Fifty years separate these two works. A lot happens in 50 years.

Hennings also included a portrait of John Pascoe Fawkner, looking as cranky as ever. He seems to be taking a stroll. Per-haps he is not cranky at all, but smiling. It is hard to tell, because a cyclorama is not meant to be viewed this way, on the floor. Lines that should be straight are curved, and curved lines seem straight. Nothing falls into perspective until a cyclorama is made vertical and round.

According to the La Trobe librarian, Dianne Reilly, the cyclorama found its way to the library in 1956, apparently as the gift of the aquarium trustees.

The cyclorama came up from the basement wrapped face-down around a pole. Now it is wrapped face-out around an aluminium pipe covered with polyethylene foam to prevent interaction between the aluminium and the can-vas. The whole thing is wrapped in foam once more. This should stop the paint from deteriorating further, Dianne Reilly says.

What is to become of this historic object? Everyone associated with it wants it restored and put on show for Victoria’s 150th birthday in 1984 and 1985. What will it cost? Nobody knows. How will it be done? Nobody knows.

Warren Horton, the State Librarian, is emphatic that any restoration work must be absolutely correct. He is patient about this, not willing to rush in. He wants to get the best advice there is.

Dianne Reilly says that if the cyclorama went on show, “we’d have queues down the street as the museum had for the dinosaurs”.

Mimi Colligan, meanwhile, has approached the Victoria and Albert Museum, which has recently restored a cyclorama (Rome, 1824). The museum is sending her plans and specifications about the way this is displayed.

At the same time, the Victoria and Albert has put a little feather in Ms Colligan’s cap. She has accepted the museum’s invitation to deliver a paper there in July on Australian cycloramas and panoramas.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article