‘I’m keen to go around again’: Chief Commissioner’s aims and admissions

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

It is the morning peak hour inside the near-new police headquarters in Spencer Street. Uniformed members flood in, most carrying takeaway coffees. Citizens mill in the foyer waiting for their cop-related appointments and detectives wearing suits and ‘don’t bother me, I’m important’ expressions power by.

No one is munching on hangover food. Times have changed.

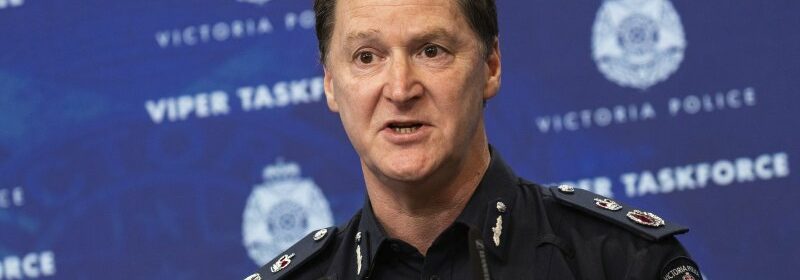

Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Shane Patton.Credit: Paul Jeffers

Thirty-seven storeys above sits the office of Chief Commissioner Shane Patton, with the best view in town. You see the bay to the Heads, the grass of Marvel Stadium (he drinks his coffee from a Bombers cup) and Flemington Racecourse.

Directly above is a helipad capable of dispatching the Special Operations Group to any crisis around the state.

It is a long way from the late 1970s, when he was a recruit and Russell Street was headquarters, with nets on the stairwell to stop suspects jumping and the Police Club around the corner serving steamed dim sims from 11am.

Patton is nearing the end of his third year of a five-year term as the boss and is up for a second term.

“If they [the government] want me, I’m here. It has had its moments, but I’m keen to go around again.”

A career police officer, he says nothing prepares you for the top job: “It is not until you sit here you know. Everyone wants a piece of you.”

You are a cop, a bureaucrat, a strategist, counsellor, figurehead, headmaster, diplomat and coach. You put out fires and then hunt the arsonist.

Yet of all his reforms it is the least important that has been the most popular: allowing cops to have beards. “The members love it, maybe it’s the hipsters.”

Not to be confused with Chief Commissioner Shane Patton.Credit:

Patton is an enthusiast (described as The Energizer Bunny by a colleague) who is wedded to a reform agenda coupled with a back-to-basics philosophy. For all the modern corporate speak, it boils down to more visible police, better connection with the local community and providing the services the public want.

Then came COVID-19. Melbourne became the most locked-down city in the world, with curfews that made law-abiding citizens into postcode prisoners. Enterprising drug dealers used the dark web to embrace the concept of working from home.

Sure, the crime rate dropped, but so did the force’s reputation. “COVID hurt us, there is no doubt. We had no playbook for something like that. We could have done better and it took some chips off us,” he says.

For policing there have been unintended consequences. For more than two years police who were considering retirement held off, Patton says, “because they couldn’t go anywhere”.

Now that bubble has burst, with a rush of retirements and resignations leaving police – despite a massive recruiting campaign – 800 cops short, creating a downward spiral. Police on the road have to fill the gaps, creating stress that results in sick leave and even more front-line gaps.

Patton says forces around Australia are struggling to find enough recruits because many alternative careers offer the option of working remotely.

“We are creating more flexibility but ultimately, you can’t drive the divisional van from your lounge room.” (Although many years ago divisional vans were driven to unauthorised nightshift barbeques.)

To build the numbers, the waiting list is being cut. Up to 40,000 people who showed interest but didn’t progress are being approached and the adage “go out and get some life experience” is being shelved. “If you are 19 and mature enough, then come on in,” Patton says.

While police are out there recruiting, they are also working to deal with their own hidden epidemic. Over 700 police are on sick leave, with 85 per cent of those cases relating to mental illness.

Patton has created a taskforce to help police get back to work, leave the force with dignity if they can’t, and teach senior cops around Victoria early intervention methods to deal with mental health spot fires before they become chronic. This includes finding temporary off-road positions for those who may be struggling.

But if people are to be rotated into non-operational spots, he has to find staff to go to the front line.

Patton met his leadership team a couple of days ago to identify worthy but non-core duties that can be scaled back in favour of boots on the ground. This means backroom strategy types will be asked to volunteer for station shifts to create some relief.

The volunteers will remove their office cardigans and whack on a vest, swap their cufflinks for handcuffs and grab a baton instead of a ballpoint.

I have known the last nine chief commissioners and while they have all been very different, every one of them wanted a more efficient discipline system to rid themselves of the corrupt, a process that at present can take years. “It takes way too long,” Patton says.

A police force is staffed by all types, from the dedicated to the bone to the bone-headed to the bone idle, and good luck trying to change it.

Patton is introducing the Discipline Transformation Program, a name that sounds rather spooky. It is, he says, a simplified model to replace 16 different complaint categories with three and create a path for groups, including Indigenous people who may not trust police, to lodge complaints through a third agency, such as legal aid services.

The fact is the least powerful are the most likely to suffer from police abuse and the least likely to complain. Bullies always pick their targets.

Patton wants a system where if the complaint is unfounded it is dealt with quickly, those who have made “silly mistakes” are educated rather than sacrificed, and the bad ones “are for the high jump”.

He takes it personally when a cop “brings the force into disrepute” and is staggered that despite massive workplace reforms there is still predatory sexual harassment, with an Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission report dropped a few days ago showing some cops are too dumb and too sleazy to change.

IBAC Deputy Commissioner Kylie Kilgour reported: “We found women experiencing domestic or family violence were targets of predatory behaviour by police officers and more than half of all cases reviewed indicated a pattern of behaviour by the perpetrator against more than one person.”

Recently, Patton sent a message to all police employees stating what he hopes is blindingly obvious.

“With this power comes great responsibility … We are all here to serve the community and set a positive example for our great organisation. That is why I will not tolerate misconduct of any kind from our employees.”

The frustration, he says, is that the majority of cops love what they do and are running from job to job. The few who can ruin it for the others should be kicked out.

The idea that cops are underfunded, underpaid and under-resourced is a myth. Victoria is now the biggest police force in Australia and has more hi-tech gear than James Bond.

All operational police will be equipped with tasers that Patton says will provide a non-lethal option that he believes will save lives. “Even producing a taser can de-escalate a situation.”

Decriminalising public drunkenness will create challenges, he says, insisting: “We don’t want to put people in cells just because they are drunk.”

New laws to stop meetings like these. Credit: Anthony Neste/HBO

A few years ago police locked up 22,000 drunks, but last year that figure dropped to 3500.

Forget the law for a minute and let’s look at the reality. A happy drunk was ignored or, if they were a bit of a nuisance, told to go home. An angry drunk would be given the chance to clear off and if they didn’t, they were put in a cell for a few hours. The philosophy is informally known as “lift home or lock them up”.

Under the new laws being drunk is not an offence but if you carry on like a pork chop (sorry vegans) you will likely be committing other offences that may justify a trip in a divvy van. “It will be tricky, but we will do the best we can,” says Patton.

There will be legal changes to assist police with that toothless tiger, the anti-criminal association law. Trumpeted by the government at the time as a game changer in disrupting serious organised crime, it will now be revamped.

As it stands serious crooks who associate face three years’ jail and fines of more than $50,000, but there are so many exceptions that not one person has been charged in the seven years the law has been on the books. “I am very hopeful there will be changes in this space, and it will become a key weapon in the future,” Patton says.

Outlaw bikies will be banned from wearing their colours, reflecting interstate laws.

One area keeping police off the road is dealing with paperwork – a problem of their own making. The fiasco surrounding barrister-turned-informer Nicola Gobbo has resulted in new disclosure rules. In short, police can no longer pick and choose what material they deem “relevant”, and must now disclose all material gathered in an investigation.

It is a nightmare that Patton hopes will eventually recede: “When lawyers have to deal with hundreds of boxes of material they will start making specific requests and not just go on fishing expeditions.”

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article