Memory man: How ‘Patto’ and his squad worked to match faces to crimes

When we look at a painting we all interpret what we see, and if we are unfortunate enough to be caught in a crime our memories capture unique (and not necessarily accurate) impressions.

For 23 years Adrian Paterson was the head of the Criminal Identification Squad, working patiently to sift through people’s memories in the hope of creating images accurate enough to identify offenders.

Adrian Paterson – 23 years putting a face to a crime.

Today the go-to is CCTV, dashcams and people who pull out their phones quicker than Wild Bill Hickok could produce his ivory-handled Colt revolver.

For Paterson and his colleagues it was a matter of interviewing and coaxing out memories from “eye” witnesses who had only seconds to remember details of offenders in moments of incredible stress.

They must have done something right, for in those 23 years CIS identified 4709 offenders – a success rate of better than one every 48 hours.

We have all tried to put a name to a face. This lot used art and science to put a face to a crime.

“Patto” was in policing for a staggering 54 years, including eight years as a part-time law instructor, retiring in 2018 at the age of 74.

He joined the Federal Police in 1964, then Victoria Police in 1970 and saw identification move from sketches and Photofit boards to sophisticated facial recognition technology.

Some witnesses, he says, see nothing but an event. “Someone is caught in an armed robbery, and you ask them to describe the offender, and they will say, ‘all I saw was a bloody big knife’.”

People need a point of reference, he says. The hairdresser seeing a robber running through a shopping centre identifies his hair colour and cut, a woman who sees a bandit says he looks like the star from the movie she watched the night before and the home invasion victim says from the back the offender looks like her son-in-law.

The boy nearly abducted from a park gives a detailed description of the offender’s dog. Locals quickly identify the man who regularly walked his pet in the area.

Sometimes a crook can just pick the wrong house, such as the time William Ellis Green disturbed an intruder in his home. Green was better known by his initials WEG, the legendary cartoonist for the Herald newspaper.

When police asked for a description, WEG let his black marker pen do the talking, banging out a quick caricature. It proved to be an accurate (if exaggerated) representation of a burglar caught in the area later that day.

A CIS investigator created an image of a sex offender after interviewing a victim. On the way back to the office he saw the offender drive by on a bike and immediately made the arrest.

One of the best witnesses Paterson interviewed was a 10-year-old country boy caught in a car in South Yarra back in 1986 when it ran out of petrol.

“The husband left his wife and child in the car while he walked off to try and find a service station. Shortly thereafter, two vehicles (one previously stolen) pulled up behind their car. Two offenders got out of these cars and primed an explosive device designed to blow up the Turkish Embassy [sic].

“The young boy, kneeling on the back seat of the family car, looked out from the back window at the activities of the two men, concentrating on one in particular.

“As a result of the subsequent explosion, the family came forward. I had the benefit of interviewing the young boy at two o’clock in the morning.

“The resulting image was one of the closest I have ever obtained from such a young witness. The likeness to the offender was amazing,” says Paterson. As a bonus, the boy was able to remember the numbers on the registration plate.

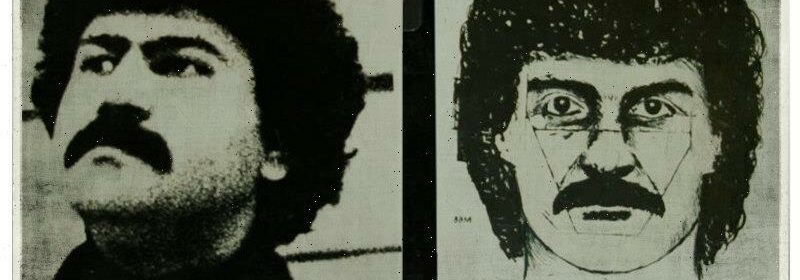

One of the terrorists was killed in the blast. The second, Levon Demirian, who was arrested and convicted, bore a remarkable resemblance to the boy’s Photofit.

The image and the terrorist. The 10-year-old boy’s description and Turkish consulate bomber Levon Demirian.

In 1997, Mersina Halvagis was murdered in the Fawkner Cemetery while tending her grandmother’s grave. Years later a witness provided a description of a suspect she saw leaving the cemetery at the time, having been struck by his sinister eyes. It was identical to serial killer Peter Dupas, later convicted of the murder.

Paterson spent more than two decades trying to move with the times, embracing computer technology and looking for the latest ways to identify crooks.

Like many specialists he had to deal with two types of senior cops: the innovative, curious and open-minded; and the stubborn, old-school dinosaurs who saw change as an affront to their training. The latter didn’t understand that by protecting the past they were sabotaging the future.

Even when Paterson lobbied for and received government seeding money for world-first computer face recognition technology it was knocked back by the woodenheads, more concerned about the chain of command than catching crooks.

The image created by a witness who was at the Fawkner Cemetery on the day Mersina Halvagis was murdered compared to the killer, Peter Dupas.

Now aged 78, Paterson has written Facing the Challenge: The Art of Identifying Offenders, based on the history of the Criminal Identification Squad, which he feels many senior police did not give the credit it deserved: “In my career I never worked with a group as committed as the CIS. We worked as a team.”

For a man who spent most of his career searching for tiny details that could unlock mysteries, it was only later in life that he found one close to home.

Only when his mother was frail and her health was fading did she share her secret. Adrian was adopted. The investigator searched for his past to find that he had four sisters and six brothers.

He was born in November 1944 and his mother’s husband was due back from the war the next month. “That’s why I had to disappear,” he says.

His adopted father put his age up to fight in World War I and down to fight in World War II. Little wonder he would be regularly hospitalised with post-traumatic stress disorder.

While working as a sign writer and clerk his adopted father urged him to find a secure job, and so Paterson joined the Federal Police. After six years he moved to the Victoria Police. In his application under hobbies he wrote “art and drawing”, at a time when most were more interested in footy and drinking. Someone must have taken notice, because it was the main reason he would eventually transfer to the CIS.

As a young cop he learned the need for thoroughness. After failing to search a seemingly harmless vagrant he was unaware the man was carrying a concealed glass. When Paterson went to remove him from the divisional van he tried to stab Paterson in the face, missing by centimetres – a lesson he would share with recruits when he was an instructor.

An image created by the CIS of a 2002 Bali bombing suspect.

When he wrestled an armed offender to the ground while off duty, his wife said that as a father of three daughters it might be a good time to go off the road for a while and so he accepted the move to CIS.

At different times there was a push to recruit non-police to fill the role of turning descriptions into images, but Paterson argued you needed investigators who could judge the credibility of the witnesses too.

Take the case of Drouin vet Mark Neilan and the 1988 murder of his pregnant wife, Kathryn.

On a Sunday in July, neighbours heard a muffled cry from the Neilans’ sprawling property and found Mark locked in the boot of his Mercedes.

Worse was to follow. His wife was found shot dead at point-blank range.

Neilan gave an elaborate story of being confronted by three armed men. The property was trashed, as was his veterinary surgery down the road, with money and drugs stolen – a classic raid by ruthless thugs.

Paterson recalls: “The ‘grieving husband’ sat with one of the CIS members and methodically and in pedantic detail described all three offenders one by one. From years of experience, it became evident that the husband’s detailed description of all three offenders was too good to be true. The grieving husband’s credibility was immediately questioned and detectives notified accordingly.”

The Neilan case as reported by The Age on September 23, 1990.Credit:Age archive

Police reconstructed the crime scene and established there wouldn’t have been enough light to see the offenders in the detail Neilan provided. All the drawers in the surgery were left open as if rifled – except you could only search them by opening and closing them one at a time. The television was upturned, although residual dust marks on the stand showed it had been smashed before being placed on the ground. There were also breathing holes drilled into the floor of the Mercedes’ boot.

When police concluded Neilan was lying, he doubled down. He reported to them that just by chance he had seen one of the offenders while shopping in Chadstone, followed him for a while but losing him before he could raise the alarm. Helpfully, he provided information for a Photofit.

Then one of the Neilans’ pet dogs was shot dead with the gun used to kill his wife – a gun that was never found.

In 1990 Mark Neilan was convicted of murder and sentenced to a minimum of 15 years.

A picture – even a false one – can tell a thousand stories.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article