On the high seas between Florida and Cuba, U.S. immigration policy a matter of life and death

ABOVE THE FLORIDA STRAITS — The twin-prop Coast Guard plane banked hard left, circling about 1,500 feet above the uninhabited Anguilla Cays, a small group of scrub-covered islands.

The buzz of the propellers sent at least a dozen people below scattering into the underbrush, leaving a rickety, apparently disabled open boat lying on a beach.

Thissliver of an island sits about 45 miles north of Cuba. The Florida Keys are still further north.

Their vessel below looked like so many others that have dared to cross these blue depths, hoping to make it from Cuba or Haiti to U.S. shores.

The trip is perilous in the best conditions, but on this recent day, gale-warning weather has whipped the sea into a white-capped fury.

Lt. Spencer Zwenger, a 30-year-old Coast Guard pilot, peered out his window. The crew’s headsets crackled: “We’ve got a group of people.”

The flight crew’s first order of business: Figuring out if the people on the island were injured or needed the Coast Guard crew to drop food and water.

This weekend patrol in Januarycame amid a recent spike in migrants fleeing political and economic crises in Cuba and Haiti by crossing the dangerous Florida Straits, many in overloaded, homemade open boats — some made of scrap wood, styrofoam and rusty car motors.

Nearly 5,200 Cuban migrants were interdicted at sea since Oct. 1 – compared with more than 6,100 Cubans intercepted during the entire last fiscal year, and 838 in the preceding year, according to the Coast Guard.

In all, almost 8,000 Cubans and Haitians were interdicted since August — about 50 per day. That’s compared to 17 per day in the prior fiscal year and 2 per day in 2020-21.

In South Florida, it has created a steady drumbeat of headline-making landings, sea rescues by passing cruise ships and complaints of strained resources by Monroe County Sheriff Rick Ramsay, who said the Florida Keys were grappling with 10 landings a day. More than 200 abandoned vessels, known as “chugs,” litter the shorelines.

Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis on Jan. 6 called up the National Guard to aid in surveillance after more than 700 migrants arrived in the Keys over New Year’s weekend, including 337 at Dry Tortugas National Park.

Now officials are hoping that President Biden’s new immigration policy for migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela and Nicaragua – announced just over two weeks ago that included a new path for legal entry – will deter these sea migrations in addition to stanching the far larger number of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexican border.

More: Miami Republicans’ plea for help from Biden official wades into partisan immigration chasm

While the program also aims to turn back more such migrants at the land border, that goal can be more complex for those who arrive by boat.

Sebastian Arcos, associate director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University, said it’s too soon to judge the policy’s impact. But the threat of becoming ineligible to apply later for parole and other changes may discourage rafters over time.

Still, with no end in sight for the increasingly dire economic and political problems driving the crossings, others aren’t so sure.

“The Cuban people are so desperate. They’re going to continue; that’s not going to stop,” said Raul Gonazlez, managing director of a Miami clinic providing migrants with medical and social services.

To be sure, the migrants arriving in South Florida by boat are only a fraction of the 220,000 Cubans stopped at the U.S.-Mexican border in the 2021-22 fiscal year, almost six times as many as the previous year.

Still, in South Florida, the increase has gained plenty of attention amid a long history of boat migrations and the magnifying glare of America’s politicized immigration debate.

For now, the life-and-death stakes for migrants undertaking such voyages, and attempts to both block and rescue them when needed, continue to play out in the Florida Straits.

More: Cubans, Haitians are fleeing to US in historic numbers. These crises are fueling migration.

‘A risk you take’: Crossing the Florida Straits

Near Tavernier in the Florida Keys last week, several abandoned migrant boats sat on the shores of a sandy park, waiting for removal.

One hull was made of wood, flattened scrap metal and a tree branch for a mast. Another was made of layers of wood, old surfboards and styrofoam. Yet another, with high-sided wood planks, was beached outside an upscale home.

It was just such a boat that delivered 21-year-old Ibrahim Delgado Baragano, along with more than a dozen others, about 40 miles away near Marathon in the Florida Keys on Jan. 10, he told USA TODAY.

The father of an infant child, living in near Matanzas, Cuba, said he faced police harassment and had lost hope he would find jobs or a future. Last fall, he decided to chip in with neighbors to build a boat.

It took four months to cobble together the wood, aluminum and an old auto engine. All the while, they worked to keep it hidden from authorities.

All around him, Cuba was facing a dire economic crisis, a function of a mismanaged state-run economy hit hard by the pandemic and sanctions. For residents, it has meant shortages of food, fuel and medicine, as well as power blackouts and skyrocketing inflation.

The Cuban regime’s harsh crackdown on rare protests in July 2021 further extinguished hope for many residents that things would ever change, experts said.

In a growing exodus, most Cuban migrants traveled to Nicaragua, which stopped requiring a visa for entry, on their way to the U.S.-Mexican border. Once they are paroled into the U.S. as their cases proceeded, the Cuban Adjustment Act allows them to apply for a green card after a year.

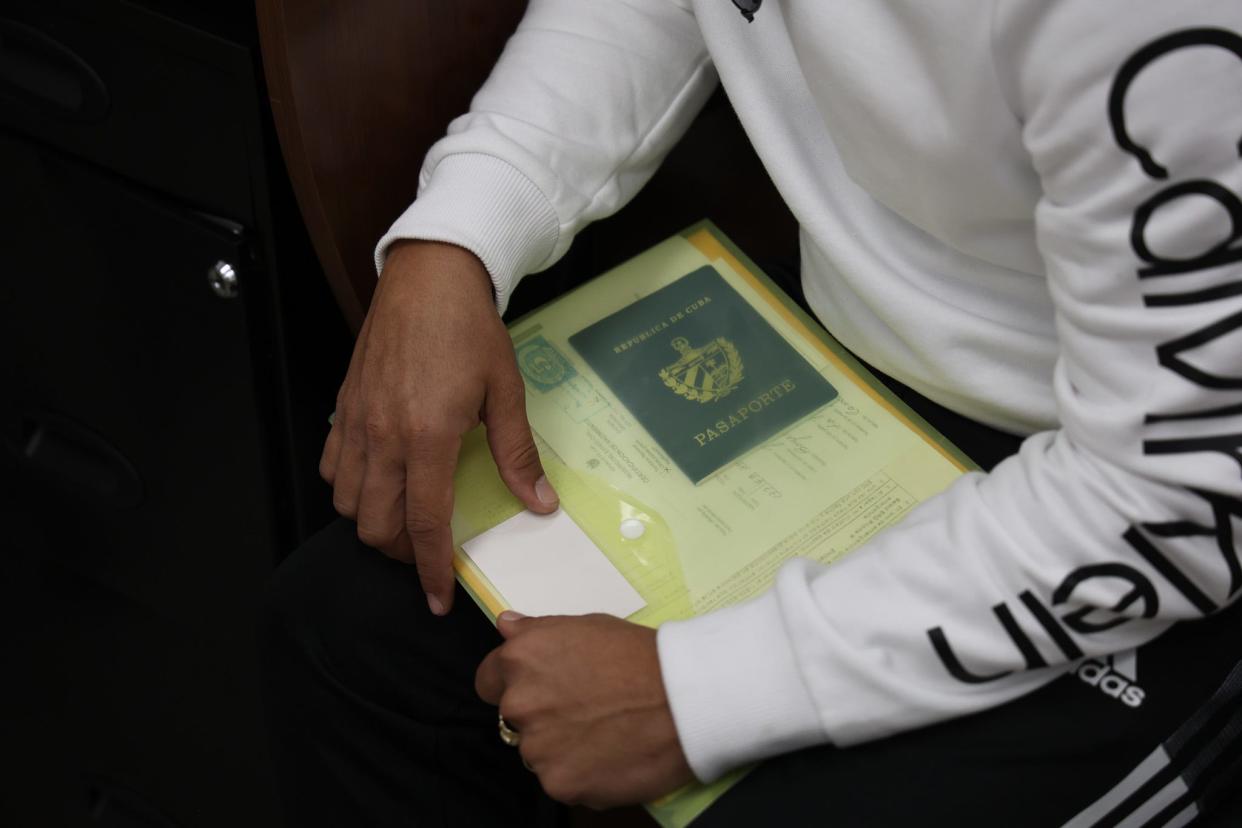

But Delgado Baragano didn’t have a passport for that trip, he said. Others who take to boats lack the money for the land trip, which can cost upward of $15,000, or family in the U.S. to help.

He knew people who had disappeared on the ocean crossing, so he left his partner and daughter behind. But he decided it was worth the gamble.

“It’s a risk you take,” he said.

After one attempt failed amid poor weather, Delgado Baragan said he and other passengers hid on the Cuban coast for nearly a week until it cleared. He said that’s why they didn’t hear about the new policy.

On Jan. 8, he said, they slipped away before dawn with some water, food, clothing and a few inner tubes if they went overboard.

At one point the weather turned foul and it rained heavily. The sea was rough. People were vomiting and grew dehydrated.

“We were really scared,” he said.

He once heard a Coast Guard plane buzzing overhead, but it apparently didn’t see them.

They reached a beach in the Florida Keys on Jan. 10, some fellow passengers whopping and hugging as they jumped out.

U.S. Immigration officials processed and released him, his paperwork showing that he would be put into removal proceedings. He said he is seeking asylum. The stakes are high.

Under the new policy, if he’s sent back, he’ll be ineligible to apply for the new parole program.

Will Biden’s new immigration policy deter sea migrants?

Just before 2 p.m. on a January Saturday, Zwenger, 30, and his copilot, Lt. Commander Josh Mitcheltree, 40, rolled their gear towards the HC-144 at the tarmac of the Coast Guard’s Miami airbase.

As they taxied toward takeoff, two more Coast Guard members — one snacking on a tin of Pringles — sat behind them at large video terminals where they monitored radar and high-powered thermal imaging cameras.

In the rear of the small plane, ready-to-drop packages of food, water, rafts and radios were hooked to parachutes, ready to deploy any migrants who were endangered in foundering boats.

The crew had seen plenty of dangerous crafts, including one powered by motors from two weedeaters. At least 65 migrants have died at sea since August, according to officials.

In recent months, federal and state agencies have stepped up enforcement efforts.

Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Mark Cobb urged people to turn to legal, safer pathways. “Don’t put your life at risk by taking to the sea when you don’t have to,” he said in a statement.

Despite the plane’s high-tech surveillance technology, finding such boats isn’t easy. Some smaller boats don’t show up on radar. And there are many more of them.

The number of Cuban migrants being stopped at sea is at its highest since 2016, just before President Obama ended the U.S. wet-foot/dry-foot policy, which granted parole to Cubans reaching U.S. soil.

Migrants interdicted at sea — and found to be without a legal basis to enter the U.S. — are repatriated, under agreements with Cuba. Those who reach land are processed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Last year, many were released with a pending case and required to check in with authorities, advocates said.

They can also seek asylum hearings before a judge to attempt to prove a credible fear of persecution.

Biden Administration’s new policy, aimed largely at the southern border, offers a safer and legal path for Cubans, Haitians and Nicaraguans, along with Venezuelans. They can apply online for humanitarian parole, available for up to 30,000 people a month from those four countries if they pay their airfare and find a U.S. financial sponsor.

At the same time, it promises to turn back such migrants from those nations at the U.S.-Mexican border without a legal basis for entry. While that can’t be as easily done for maritime arrivals, another part of the policy threatens those who arrive illegally with giving up a shot at the new parole.

“Cubans and Haitians who take to the sea and land on US soil will be ineligible for the parole process and will be placed in removal proceedings,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said in a statement this week.

It’s not yet clear whether deportations flights to Cuba will become more common and act as a deterrent, Miami immigration attorneys said.

Customs and Border Patrol officials declined to comment or provide figures on how many apprehensions of sea migrants had taken place since the policy went into effect.

But on Friday, the Coast Guard said that within the preceding week, authorities had halted 244 migrants at sea and apprehended or encountered 200 who had made landings. More than 260 people were repatriated to Cuba had Haiti in that time.

Experts and advocates disagree on whether the new parole program will ultimately change the numbers of migrations.

But Miami-Dade County Commissioner Marleine Bastien, a longtime Haitian community and immigration advocate, predicted the new parole visas will go to middle-class migrants with passports and means – and not the poor who are more likely to take to the sea.

“You must address the root causes of migration. That’s the only way” to reduce it, she said, calling for U.S. assistance to stabilize Haiti where she said residents face a “war-like situation.”

New rules bring opportunity, tough choices

Inside an aging office tower in downtown Miami — a crucifix hanging on the wall — a crowd of mostly Cuban men and women, one pushing a baby stroller, clutched papers in folding chairs this week.

At the Catholic Legal Services office, many migrants seek help pursuing asylum and other issues. Those arriving in recent months face a slew of challenges: Rising housing costs, strained social services, long waits for asylum hearings.

The area is home to a sizeable portion of the more than 200,000 Cubans arriving 2021-22 fiscal year — a bigger Cuban exodus than the Mariel boatlift, which saw 125,000 Cubans flock to South Florida shores on boats over six months in 1980.

Many will still arrive under the new parole policy, said Director Randy McGrorty. But he also expects deportation flights to Cuba to resume sometime soon, which could include recent migrants. Cuba in November said that it would receive such flights, which were stalled in the pandemic.

But he said it was imperative to allow new arrivals, including those from Cuba, a chance to make cases for asylum. That’s been a major concern of immigration advocates who have criticized Biden’s policy.

“People will say the prime motivation (for migrating) is economic, rather than political,” he said. But because Cuba’s “government, society and the economy are all controlled by a unified force, it’s hard to separate them,” he said.

Already, the new parole visa program has had Cubans lining up at the U.S. Embassy in Havana, which recently resumed processing migrant visas. Haitians have also reportedly been applying for passports to start applications. And some have already been accepted into the program.

That has provided a “light at the end of the tunnel,” for friends and family back in Havana, said Jose Luis Suarez, 33, who crossed at the Mexico border three days before the new policy would have turned him back.

“Everybody is trying to get a sponsor to come to the United States,” he said during a visit to a bustling Integrum Medical Group which offers a clinic and social service center for migrants that Raul Gonzalez opened in 2019.

At the same time, people without a required U.S. sponsor, who lackmeans for airfare or who lose out as demand outstrips the supply of visas might still take to the sea, Gonzalez said. The desperation to flee places like Cuba or Haiti, he said, should not be underestimated.

More than 15 years ago, he was a doctor in Cuba earning just $10 a month. Despairing after the Cuban government denied him a chance to emigrate, he decided to flee by boat. He tried unsuccessfully nine times before finally winning a visa.

Oasis Pena, who works with Gonzalez as well as Miami’s nonprofit Immigrant Resource Center, said the forces pushing people out of Cuba are likely to remain — and with them, the risks she too knows well.

During the “balsero” crisis in 1994 — when 35,000 Cubans took to rafts after anti-government protests led Fidel Castro to say that “whoever wanted to leave, could go” – Pena accompanied Brothers to the Rescue, a group of Cuban exiles who flew planes to spot migrants and Coast Guard for rescue.

She recalled how difficult it was to spot tiny makeshift boats amid the waves and water trying to drop supplies to them.

At sea, the search goes on

Those same challenges existed for Zwenger and Mitcheltree – who on a recent day were circling the likely migrants on Anguilla Cays, part of the westernmost Bahamas.

It’s one of the places where migrants make stops or seek out during poor weather or engine trouble. In 2021, the Coast Guard rescued three Cubans in the area who had been stranded for a month after their boat overturned, surviving on coconuts, authorities said at the time.

Now, watching this group near what appeared to be a homemade and potentially disabled boat, the flight crew debated dropping supplies. They radioed a Bahamian fishing boat nearby. After several tries, the captain answered.

The fishing boat had sent a skiff that carried food and water to the people on the island. The pilots asked about health concerns, but the boat captain said they were OK.

With the people below seemingly safe for now, the team would report the sighting to Bahamian officials. They, or a Coast Guard cutter, would be dispatched. Help would be on the way, whether the group wanted it or not.

The day’s high seas meant they weren’t going anywhere soon.

The pilots circled a little longer, then climbed higher and flew on amid a falling late afternoon sun, still looking.

Contributing: The Associated Press

Chris Kenning is a national correspondent. Reach him at [email protected] and on Twitter @chris_kenning.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Cubans face a life-or-death journey as U.S. immigration policy shifts

Source: Read Full Article