The sinking of a hospital ship, when time was frozen forever

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

In the depths of the Coral Sea, about 80 kilometres from Brisbane and 44 kilometres east-north-east of Point Lookout, North Stradbroke Island, time stopped 80 years ago.

The Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, blown apart by a torpedo from a Japanese submarine, plunged 550 metres to the sea floor, taking 268 lives, including 11 army nurses, with her.

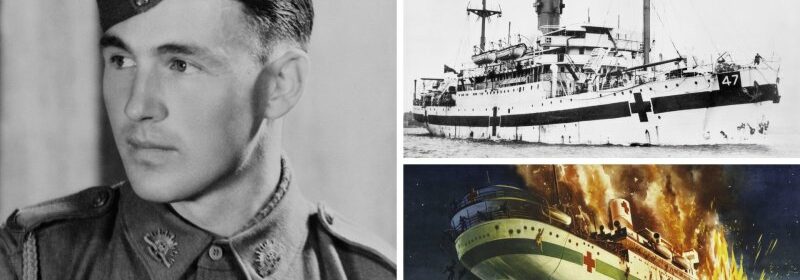

The AHS Centaur, sunk by a Japanese submarine off the Queensland coast 80 years ago this Sunday.Credit: Australian War Memorial

Among the 64 survivors plucked from the shark-filled ocean 35 hours later was a driver attached to the 2/12th Field Ambulance, 26-year-old George McGrath, of Braidwood, NSW.

McGrath, blown from sleep by the explosion, managed to leap into the sea as the Centaur went down.

There, he floundered naked, wearing only his Swiss-made wristwatch.

The timepiece, with radium glow-in-the dark numerals, stopped working the moment seawater flooded its working parts.

McGrath kept the watch close as the years did their destructive work.

George McGrath’s watch, which stopped at the hour of the sinking.Credit: Australian War Memorial

Half the watch face became discoloured and the hands rusted off, though the numbers remained radioactive: radium has a half-life of 1600 years.

Study the watchface closely, however, and you will discern the rusted imprint of the large hand at 2, the small one at 4.

George McGrath.Credit: Australian War Memorial

Time, then, stopped at 4.10am on Sunday, May 14, 1943, as the Centaur disappeared beneath the sea.

McGrath died in Canberra in 2006, the last of the survivors of the hospital ship.

Years before he was gone, he ensured his old watch would continue to remind of the precise moment when the Centaur went down with 178 of his comrades from the 2/12th Field Ambulance, all but one of the nurses on board, and most of the ship’s crew.

McGrath donated it to the Australian War Memorial, where this weekend it will be on display with a precious few other artefacts from the Centaur: flares, life jacket lights, a scalpel, and several other watches worn by survivors who treasured them.

It was to Australians at the time more than a tragedy: it was a clear atrocity and a war crime.

The Centaur’s white hull was adorned with a green band interspersed by three large red crosses on each side. Other large red crosses were placed so the vessel’s identity as a hospital ship would be visible from sea and air. The internationally recognised markings were illuminated at night by powerful floodlights. The International Committee of the Red Cross had informed the Japanese high command of all these details.

Yet in the hours before dawn, the ship of mercy – fitted out to transport wounded soldiers from New Guinea to Australia – was stalked by a Japanese submarine.

Minutes after 4am, the sub’s commander let loose a torpedo that blew a great hole in the Centaur, setting its fuel tank alight. It took three minutes for the ship to roll and sink, bow first, with most aboard trapped.

The few survivors, some of them burned and wounded by flying steel, clung to two damaged lifeboats and rafts cobbled together from wreckage.

They saw ships in the far distance, but failed to gain their attention. The following night, survivors believed they saw a submarine surface nearby.

One of the survivors prepared to fire a distress signal when his companions stopped him, fearing it was the Japanese submarine returning to the scene. It was a wise move.

The submarine that sank the Centaur was, according to an official Japanese history produced after the war, the I-177 under the command of Hajime Nakagawa.

Though Nakagawa was never charged with that particular war crime – Australian investigators couldn’t find enough incontrovertible evidence in time – he was found guilty of ordering the machine-gunning of survivors from torpedoed ships on three different occasions while commanding a different submarine.

Sister Ellen Savage, survivor of the Centaur.Credit: Australian War Memorial

He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment as a war criminal. He reportedly died in 1991.

The nurse who survived, Sister Ellen Savage, was hailed nationwide as a hero. Though suffering burns, a fractured jaw and broken ribs, she rallied fellow survivors in her liferaft and took their minds off the circling sharks and absence of food and water by organising a sing-along.

Eventually, the American destroyer, USS Mugford – itself a survivor of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941– rescued the Centaur castaways.

Savage was awarded the George Medal for her courage.

The vision of nurses trapped and drowning in the Centaur lit great passions across the nation, and a famous wartime rallying poster called for Australians to “Work, Save, Fight, and so Avenge the Nurses!”

The director of the Australian War Memorial, Matt Anderson, said the impact on Australia of the loss of innocent life on the Centaur was so great and lasting that artist Napier Waller incorporated a depiction of a mythical centaur in the mosaic of the servicewoman in the Memorial’s Hall of Memory – the only reference in the hall to a specific event.

The poster created after the Centaur’s sinking.Credit: Australian War Memorial

The final resting place of the Centaur was not located until 2009, and is now protected as a war grave.

All along, George McGrath, the shipwrecked driver with the Field Ambulance, tended the memory of a hideous moment imprinted on the face of his wristwatch: time frozen forever.

The Australian War Memorial will host members of the 2/3 Australian Hospital Ship Centaur Association at the Last Post Ceremony on Sunday, the 80th anniversary of the sinking.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article