As a child of immigrants, my choice was clear: be a doctor or be a disappointment

By Jess Ho

I was raised to have no personal ambition. Instead, I was culturally required to fulfil my obligations. They were the expectations my parents had for me as an immigrant child after settling in a dusty, foreign land. My parents, like thousands of others, left Hong Kong in the years leading up to the handover for a country they had never even visited before. They went searching for a better life and placed all their hope in the only thing they’d ever known: the Commonwealth.

They had ambitions that couldn’t be fulfilled in one of the world’s most densely populated financial hubs as it entered a period of undefined, and potentially non-democratic, rule. They gave up their jobs, packed up their lives and fled to an outer suburb of Melbourne in the 1980s. They had two children. First, my sister. Then, me. Before we were even born, they defined our paths for us. Our options were: doctor, lawyer, engineer, or disappointment.

It’s a long-running joke to be the Disappointment Child when you’re an Asian kid. It is what most of us end up as. It’s not just that we have failed to climb the social and economic ladder, bridging the gap between minimum-wage immigrant and highly educated, white collar, respected member of society in a single generation – it’s also because we have wasted all the time, money and sacrifice that was spent to get us there.

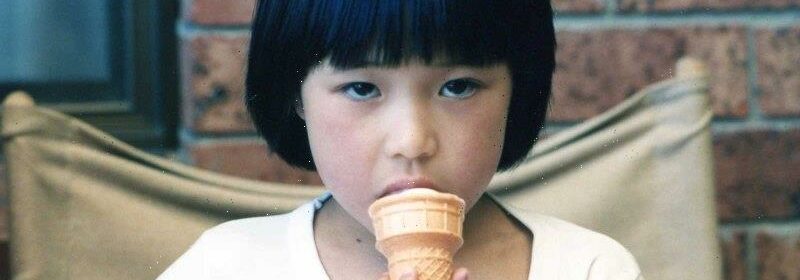

Jess Ho as a child: “I had no hobbies, no personality, and no friends.″Credit:Courtesy Jess Ho

I had no childhood. As soon as I was capable of sitting upright without assistance, I learnt to play the piano. When I wasn’t at school, I was practising scales, learning pages of sheet music, how to sight read and memorising bars at a time, every day of the week.

On Saturdays, I went to Chinese school to learn how to speak and write in Mandarin. After, my sister and I would be carted off to tutoring. This wasn’t extra study to help us catch up on subjects we didn’t understand. It was advanced, out-of-school education, learning the curriculum years beyond the standard syllabus to help us either earn scholarships to private schools, a place in the state’s highest ranking selective school, or to ensure we graded the highest in every class we took.

On Sundays, we went to church. I was drowning in homework, exam preparation and piano practice. I hated it. I had no hobbies, no personality and no friends. I was socially inept because I couldn’t relate to my peers. I was constantly frustrated in class because the other kids didn’t automatically grasp ideas, concepts and structures as soon as they were laid out for them. The teachers sent me to the library so I could “independently study”, which was another way of saying, “Stop discouraging the other students for being normal”.

By the time I did my VCE, I was burnt-out. I was depressed. I was sick of institutional learning and I didn’t care about my TER score. I knew I would make a terrible doctor, lawyer or engineer because I was (and still am) an antisocial germaphobe who is not great with numbers. It was too late for my sister. She studied physiotherapy at university but cut her career short because it wasn’t until she graduated that she realised she didn’t enjoy treating people.

I realised that being beholden to my parents’ dreams was as much a dead end as not fulfilling them. I had to realise what I wanted out of life.

Jess Ho: “By the time I did my VCE, I was burnt-out.”Credit:

I hid myself in a creative arts course so I could dissect thought processes, the human condition and creative connection. I immersed myself in people and practised human interaction. I inched my way towards a sense of self. I was fascinated in observing individuals, trying to understand them, their motivations and actions.

I watched people obsess over fine details and break down over imperceptible imperfections. I saw pride, ego and greed in the strangest forms. I strived to emulate the kindness, greatness and strength I saw in others, all the while stumbling through a range of vocations.

I’ve been a student, a waiter, a business partner, a business owner, an editor and a reviewer. I was good at them, too. But being good at jobs didn’t give me a sense of accomplishment. Because for all these titles and the ambitions my parents tried to force on to me, I didn’t find pleasure in chasing external approval. My aspirations are constantly shifting because I’m pursuing internal fulfilment.

It sounds simple, but all I desire to be is a good person who is happy. After all, when my parents left everything they’d ever known for something better, shouldn’t that something better be as basic as happiness?

Jess Ho’s memoir, Raised by Wolves, published by Affirm Press, is out now, $29.99. She takes part in Food for Thought at the State Library on September 10 for the Melbourne Writers Festival. The Age is a festival partner. mwf.com.au

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article