Julian Rubinstein’s “The Holly” continues to rile Denver’s power structure

The ongoing war between Denver’s Bloods and Crips gangs crescendoed in May 2008 when the Holly Square Shopping Center burned to the ground — retaliation by the Crips, neighborhood residents said, for a killing by the Bloods.

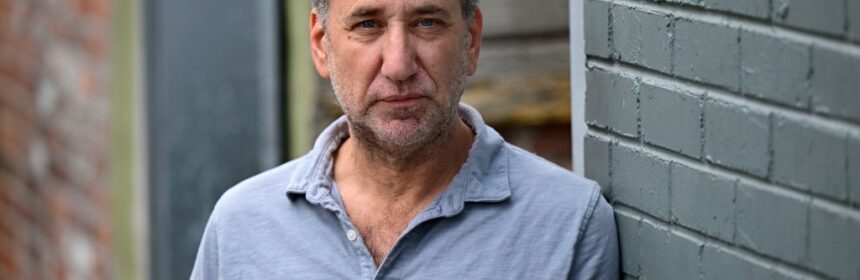

The fight for that Northeast Denver community hub, which continues to anchor one of the city’s oldest Black neighborhoods at 33rd and Hudson streets in Northeast Park Hill, became the story of “The Holly: Five Bullets, One Gun, and the Struggle to Save an American Neighborhood.” The nonfiction book and documentary are the work of Denver native Julian Rubinstein, who was so engrained in the story that he briefly went into hiding after the book was published due to threats on his life.

Like the book, “The Holly” documentary was filmed as the 53-year-old Denver native dove into his years-long reporting project with a love for and personal stake in his home city, but no political agenda, said Rubinstein, who’s currently a visiting professor at the University of Denver.

“The Holly’s” main character is Terrance Roberts, an anti-gang activist who devoted his life to lifting up The Holly after he was released from prison. The story took a bizarre turn in 2013 when Roberts was charged with attempted murder for shooting young gang member Hasan Jones during a peace rally at The Holly.

A court later found that Roberts acted in self-defense and, as of a few months ago, Roberts is running for Denver mayor, giving “The Holly” the feel of an up-to-the-minute civic primer as much as riveting, true-life drama. Since it was published in 2021, the Colorado best-seller also has been acclaimed by outlets such as The New York Times (it was an Editor’s Choice there) and, in July, won the Colorado Book Award for general nonfiction.

Now, the documentary is starting to make the rounds on the festival circuit, having nabbed the Audience Choice Award in its world premiere at the Telluride Mountainfilm festival this summer, and been picked up by executive producer Adam McKay (“Don’t Look Up,” “The Big Short”). Denver audiences will get a chance to see the gritty, heart-wrenching film when it plays as part of the 45th Denver Film Festival, Nov. 2-13 — essentially the first title to be announced for the event.

But first, Rubinstein will appear at the Denver Press Club on Thursday, Sept. 8, to discuss the book alongside Roberts and Emmy-winning moderator Tamara Banks.

We caught up with Rubinstein in advance of the 7 p.m. event at 1330 Glenarm Place, which is open to the public and free for students and members; it’s $5 for all others. Visit denverpressclub.org for more information.

Q. You took a deeply embedded approach to this story. How did you choose it?

A. It’s my second book, and I choose my subjects very carefully because I know how hard and long it might be. I read about this in New York and moved back home for it. I could make a list of all the challenges, including being seen as a white guy doing a story about a Black community, and having to go in and gain the trust of people in a clearly dangerous situation. I’ve done reporting on criminal justice and corruption around the world, but I wasn’t expecting to feel endangered in my hometown.

Q. “The Holly” explores the way police informants are used, and the troubling relationship some of Denver’s Black community leaders have with police leaders. How do you make sense of that for readers and viewers?

A. Through a historical lens, and that’s why the book is a multigenerational story. I couldn’t help but notice these cycles that kept continuing in this particular neighborhood and others like it, where there would be activism, pride, police operations, crackdowns and violence. What I found astonishing is the (role of) people who you think wouldn’t have anything to do with power structures in this city. You have street-gang members committing violence who are also connected to powerful people, and highly funded federal anti-gang programs that have people posing as anti-gang activists when they’re clearly not.

Q. As you’ve said before, these same problems are going on in other cities, but they seem to be playing out more publicly in Denver.

A. Most of these things are happening in the shadows, and that’s purposeful. I knew this story was going to highlight historical and political themes, but it really, really illuminates the problems with institutional racism, the criminal justice-industrial complex, and how Denver has become highly tied to both developers and federally funded criminal justice efforts — which are sometimes closely connected. It’s a new way to see the city.

Q. I get the sense that people from all sides are trying to shut Terrance Roberts up both because of who he is and what he represents.

A. A lot of people in Denver weren’t ready for him, and he can be really difficult to some people. But he sees it as his responsibility to put himself out there and say these things others weren’t saying, and that he knows are dangerous to say.

Q. What were some things that didn’t make it into the book or movie?

A. There’s a funeral that’s barely in the movie that involves the murder of a young girl by Hasan Jones, and we were actually given permission to film there with signed waivers from everyone. But even the (director of photography) who worked with me that day, who is Black, and other people who gave me feedback said it seemed too exploitative. We weren’t trying to use it that way — I was there weeping that day, I was crushed — but it’s one of the ways in which we pulled back. I wanted this to be through the eyes not of a white person or someone who’s trying to paint things this way or that way, but of a journalist.

Q. Your brother is Dan Rubinstein, the prosecutor in the Tina Peters case in Mesa County, who’s also received death threats for his work. This must be a surreal time for you both.

A. (Laughs) We’ve had this really weird year together. But we do feel like we’re part of this. I was 2 years old when my family moved to Denver in 1970. My dad was an Air Force base psychiatrist and came to do a residence at the University of Colorado Medical School. I’m a part of this community.

Q. How do you feel about the documentary coming out as Roberts is running for mayor?

A. I thank God that my book missed the deadline by two years. That last scene in the documentary — where Terrance is marching for Black Lives Matter and Elijah McClain — underlines all of these themes. The more time you spend on it, the less money you tend to make, but the better it is because it has more breadth and scope. I feel like it came out at exactly the right time.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

Source: Read Full Article