Public expects an Andrews’ victory despite disenchantment

Ten weeks to the state election and the latest public opinion polls have provided a reading of Victoria’s political temperature. Though their margins vary, these polls are in unison in finding that the Andrews government is on track to be re-elected in November.

The polls are not unvarnished good news for Labor. They suggest a significant decline in the ALP’s primary vote from the 43 per cent that it received at the last election of November 2018. But at least some of that fall is expected: Labor was never going to match the heights of support it reached in the “Danslide” of four years ago.

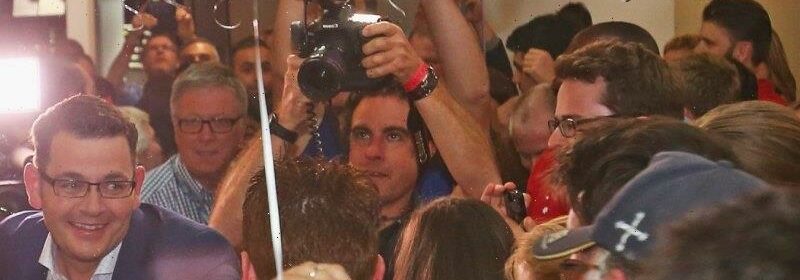

Labor supporters surround Andrews as he prepares to make his victory speech after the so-called “Danslide” in 2018.Credit:Scott Barbour

The resilience of the Andrews government’s position is arguably remarkable given the context. Consider that this is an eight-year-old administration headed by a premier with a domineering reputation, a government prematurely aged by spending much of this term in crisis mode managing the pandemic, that the ALP was the subject recently of adverse findings by IBAC and the Ombudsman, that on Labor’s watch the health system is ailing and there is a burgeoning list of infrastructure project delays and budget overruns, and that there is a prevailing mood of disillusionment with the major parties as vividly demonstrated by the federal election.

Disenchantment with the established parties will create volatility in November’s election with local-based insurgencies disrupting the traditional Labor versus coalition contest. Though not attaining anything like the visibility achieved by teal candidates in the federal campaign, independents will enjoy some success. Similarly, the Greens are poised to gain extra representation in the next parliament.

Even so, these latest opinion polls bely the narrative that Labor is in danger of being reduced to minority government. Rather they indicate that the most probable outcome remains the ALP being returned to majority government. The public assumes a Labor victory. The Resolve Strategic poll found that 53 per cent expected it to win the election while a meagre 18 per cent believed the Coalition would win.

For the Coalition, the polls are deflating. They corroborate recent remarks by soon to be former Liberal member for Kew, Tim Smith, who bemoaned that his party has treaded water this term. Michael O’Brien’s deposal one year ago and Matthew Guy’s resurrection as leader shows no sign of having remedied this situation.

The Greens are set to pick up seats at the forthcoming state election.Credit:John Woudstra

In this second incarnation, Guy has recognised the necessity to hew towards the political centre in Victoria following his woefully misjudged 2018 law and order crusade. The embrace of climate change action exemplifies Guy’s new moderated face. Yet this attempt at reinvention does not appear to have persuaded the public of his fitness for the premiership. He also has the misfortune to be fighting this election at a time when the Liberal brand has been sullied Australia wide by the baneful legacy of Scott Morrison’s prime ministership.

Indeed, it is not too much to say that an aura of failure surrounds the Victorian Liberal Party. Should the Coalition be defeated this November condemning it to opposition until 2026, it will have been victorious in only one election in nearly a quarter of a century. Nor are its struggles confined to the state sphere. The Coalition has won the two-party preferred vote federally in Victoria only twice since 1980. In short, it is a record of chronic electoral underperformance.

Putting partisan allegiance aside, it is troubling that the contest for the government benches has become so lopsided in Victoria. The story of recent decades is an inversion of the post-Second World War era when the Liberal Party was supreme (it won an extraordinary nine consecutive elections between 1955 and 1979) while Labor languished seemingly permanently in opposition.

The rotation of office is one of the things that guards against the concentration of authority in a polity. If one party monopolises government there is a danger that it becomes conceited and bloated with power. Its tentacles spread far and wide. The public service grows habituated to serving that side of politics and is remodelled to do its bidding. Similarly, a long-term government’s acolytes become ubiquitous in agencies throughout the state.

Equally, if one side of politics is exiled from office too often then this can atrophy its capacity to be either a potent opposition or viable alternative government. It grows torpid and drained of talent. In-fighting over the spoils of defeat becomes a substitute for constructive purpose.

Thankfully, operating outside the major party arena, crossbench members increasingly play a role in energising our political system and provide an alternative layer of accountability. A prime example in Victoria has been the Reason Party’s Fiona Patten who has been a one-person ginger group prodding the Andrews government to better outcomes on various social policy fronts.

Nevertheless, what is presently tantamount to a one-party government system is an unhealthy state of affairs. It took federal intervention in the Victorian ALP at the beginning of the 1970s to usher in root and branch reform that ultimately ended its long barren years. Should the Liberal Party be uncompetitive at November’s election then it may be overdue for an equally drastic overhaul. From where that shake-up would originate, however, is unclear.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article