Archie Roach’s music helped heal not just his own wounds, but those of countless others

ARCHIE ROACH 1956-2022

The day that came to define Archie Roach occurred when he was only four. This was in 1960, when government agencies forcibly took him and his siblings away from their parents.

In his autobiography, Tell Me Why, Roach recounts a memory that came back to him many years later of his screaming father being restrained by a policeman while the children were loaded into a large black car. That was the last time he saw his parents.

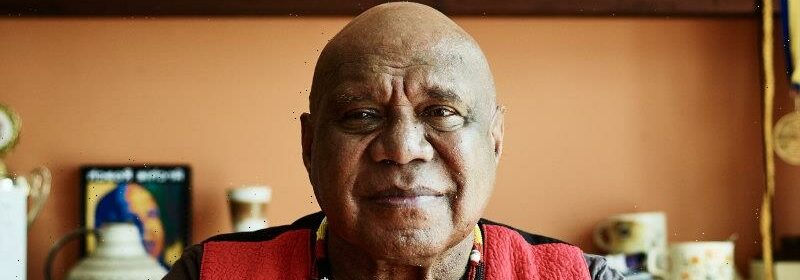

Prolific Aboriginal singer-songwriter Archie Roach has died aged 66.Credit: Kristoffer Paulsen

Life as a foster child was his new reality until he was 14, when a letter from older sister Myrtle told him his mother had died and his father was already dead.

This was the first he knew he had a family beyond Dulcie and Alex Cox, who had raised him for nearly a decade. Myrtle’s letter plunged him into a chasm of resentment and anger.

Only much later would he find redemption in the love of his soulmate and wife, Ruby Hunter, and in music.

Took the Children Away, the powerful song he penned in 1988, helped heal not just his own wounds, but those of countless other stolen generations members. Released in 1991, it reflected Roach’s gift for writing and singing with warmth, truth and an open heart, and was the first song ever to win an international Human Rights Achievement Award.

Archibald William Roach has died surrounded by his family and loved ones at Warrnambool Base Hospital after a long illness. He was 66.

He was born on January 8, 1956, in Mooroopna in central Victoria, to Archie Roach and Nellie Austin, who had married in Lawrence, NSW, in 1939.

His father, known as “Snowball”, achieved some success as a professional boxer, and the couple already had two boys and four girls when Archie arrived. They moved to Framlingham Aboriginal Mission in south-west Victoria, from where Archie – affectionately known as “Butter Boy” – and his sisters were stolen. He spent time in an orphanage and two ill-judged foster homes before his luck changed with the Coxes, Scottish immigrants with a fondness for music who lived in Melbourne’s north-west.

He attended Strathmore North Primary School, and began to sing, both in church and along with Alex Cox’s favourite Scottish airs. He fell for the music of Elvis Presley, Fats Domino and Hank Williams and was given a guitar. Life seemed good.

He was in class for his favourite subject, English, at Lilydale High School, when “Archibald William Roach” was called to the school office. Somehow he knew this was him, even though he was Archie Cox. It was to receive that letter from Myrtle. His world, he said, “started to spin”.

At 15, he left school with the loose intention of finding his family, never to see the Coxes again. Having hitchhiked to Shepparton, he was arrested for pilfering cigarettes, and released on a bond that obliged him to remain there for two years, but left after six months and hitched to Sydney.

Lost and lonely, he slept rough, was routinely jailed for begging and vagrancy, and began drinking as a respite from the empty lie his childhood now seemed. By sheer chance, he met his sister, Diana, and learned about his other siblings, including that Gladys died in a car accident. Roach and Diana were separated when a magistrate forcibly deported him to Melbourne, aged 16.

There he met his sister Alma, who introduced him to his brother Lawrence and finally, Myrtle herself. He learned that the only sibling not stolen from the mission was the oldest, Johnny (or “Horse”), whom the authorities assumed was an adult.

He stumbled through various jobs, including boxing as “Kid Snowball”. When he hitchhiked to Mildura to pick fruit he was wrongly arrested for car theft in Echuca and jailed for a year, initially suffering acute alcohol withdrawals. Released after six months, he tossed a coin and hitched to Adelaide.

It was a lucky spin, because there he met Hunter, a stolen member of the Ngarrindjeri people, and he came to learn he was a Gunditjmara man. In Melbourne, Hunter conceived a stillborn child, before giving birth to Amos – an event Roach described as lighting a musical fire in him. He began absorbing the folk of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Woody Guthrie, and his beloved country music. Hunter bore a second son, Eban, and they moved to Murray Bridge, where Roach worked at an abattoir and salt lake.

He returned to Melbourne for brother Johnny’s funeral, and then was hospitalised by an alcohol-induced seizure when back in Murray Bridge. A spell at Nunga Farm, a rehabilitation facility for Aboriginal people, proved no lasting cure, and he even attempted suicide when he failed to stay dry. Hospitalised in Adelaide, he was transferred to a mental health facility. Hunter had him released and they returned to Melbourne, but the drinking didn’t stop and she left with the boys. Another seizure and another spell in hospital followed, before Roach joined AA and finally turned his back on alcohol forever.

Reunited with Hunter and his boys, he became a rehab counsellor and began to write songs, often about the plight of others. They came to him thick and fast, just sitting in the kitchen with Hunter, while the kids played. Soon he began to perform them amid a repertoire of country classics at informal gigs.

He sang Took the Children Away at the 1988 Aboriginal protest against bicentennial celebrations, and it resonated widely. Singer-songwriter Paul Kelly saw him on TV, and asked him to open for Kelly’s band at the Melbourne Concert Hall – Roach’s biggest gig so far. When Kelly proposed Roach record, he was reticent, so Hunter virtually commanded that he do it for his people, if not himself. “When one of us shines, we all shine,” she said.

Hunter began writing songs herself, including the great Down City Streets that was included on Roach’s 1990 debut album, Charcoal Lane, which won him two ARIA Awards. After the follow-up, Jamu Dreaming, he and Hunter toured from Aboriginal communities to overseas. In 2000, he participated in a show with Bangarra Dance Theatre and later sang on the soundtrack for the film The Tracker. Another key collaboration was with Hunter, Paul Grabowsky and the Australian Art Orchestra on the album Ruby, which spawned some unforgettably potent concerts. He and Hunter also co-founded Black Arm Band, a collective of Aboriginal artists with a focus on protest songs. In 2008, he played in Melbourne’s Federation Square when Prime Minister Rudd delivered his apology to the stolen generations.

Subsequently, Roach and family bought a cottage outside Melbourne. In 2009, Hunter became unwell on a flight to the UK with Black Arm Band, and was hospitalised on arrival, as was Roach the next day after a seizure. They both returned to Australia, Hunter dying shortly after. He sang at her funeral and went ahead with a Port Fairy Folk Festival performance they were to have done together. It was among the most memorable gigs of his life.

In 2010, he suffered a stroke, which stopped him smoking, although cancer had already invaded his lungs, necessitating surgery. Typically, Roach bounced back, and although needing oxygen and having a compromised strumming hand, began writing songs and touring once more. In 2014, he set up a foundation to help incarcerated Indigenous people turn their lives around.

A 2016 tour took him to Scotland, where he sought out Alex Cox’s ancestral home, tying another bow in his life. In 2018, despite being in a wheelchair, he toured Canada, where his songs resonated with the local indigenous people as they’d done in Australia.

In 2019, he released his hugely engaging autobiography, Tell Me Why, and in 2020 performed songs from the accompanying album at Sydney Festival, reuniting with Grabowsky. He continued performing into 2022.

Roach is survived by Amos and Eban and foster children Kriss, Arthur and Terrence.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article