Rampage of the 'blackout ripper' whose crimes were forgotten the Blitz

Rampage of the ‘blackout ripper’ whose heinous crimes were forgotten in the fog of war: A handsome airman by day. But in the darkness of the Blitz, Gordon Cummins carried out a sickening killing spree – and was only caught when he dropped his gas mask

The woman lying face-up in the air-raid shelter in London’s Marylebone had put up a desperate struggle. The electrician who found her one cold morning in February 1942 first noticed her torch lying on the ground, then her handbag… then her body.

Her clothes were torn, her face and neck bruised and her shoes scuffed with mortar. Her attacker had pulled her skirt up over her hips and her underwear down to her knees. Her right breast was exposed and her money stolen. She had been strangled.

The woman’s name was Evelyn Hamilton, a pharmacist originally from the North of England. It was an unlikely and tragic end for a woman whose life had been one of blameless respectability. The outbreak of war had almost bankrupted the chemist’s shop Evelyn had been managing in Essex and she was passing through London on her way to Grimsby, where she had been offered a new job.

She had booked a room at a women’s hostel and planned to take a train to Yorkshire the next morning. The last sight of Evelyn, 41, had been late the evening before at Lyons Corner House at Marble Arch, where she had gone alone for a meal and a glass of wine.

No one knows whether the man who killed her struck up a conversation with her there, or whether he had picked up her footsteps in the darkness when she left. Somehow or other she was lured, or forced, into the shelter where she met her gruesome end.

Evelyn was just the first woman to be murdered that week. For under the cover of darkness in the midst of World War II, a man who became known as the Blackout Ripper embarked on a killing spree so violent and depraved it left even hardened police shaken.

Over six days, Gordon Cummins, a 27-year-old RAF airman, killed and mutilated four women and attempted to kill two others. Such cruelty usually confers a perverse celebrity, but while most of us are familiar with the crimes of Jack the Ripper — and, indeed, the Yorkshire Ripper, who killed 13 women over a 15-year period starting in the 1970s — the Blackout Ripper has been all but forgotten.

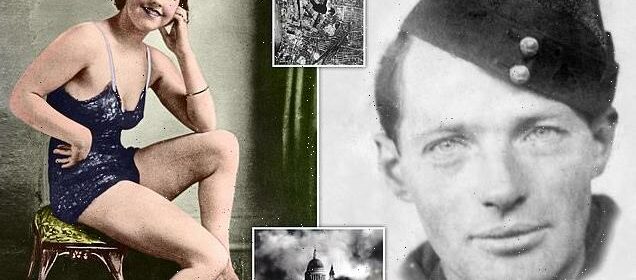

Wartime monster: Gordon Cummins (pictured), a 27-year-old RAF airman, killed and mutilated four women and attempted to kill two others in London during WWII in 1942

Evelyn Oatley (pictured) was the second victim of English serial killer Gordon Cummins. On February 10 1942, she was found strangled and mutilated in her flat in Wardour Street, Soho

Historian Hallie Rubenhold, presenter of a new podcast, Bad Women: The Blackout Ripper, believes that is because the killings happened amid the chaos of war, when death and destruction were part of everyday life.

‘The war acted as a kind of screen,’ she says. ‘The whole fabric of London was torn up and there was so much distraction, the murders passed almost under the radar.

‘What happened was shocking. It made the papers, but it wasn’t a big story, like the landings at Normandy. The women who were killed were vulnerable. Some of them were sex workers. People were sympathetic but, as with the women killed by Jack the Ripper, there was that underlying feeling: ‘What did they expect?’ ‘

Women who were on their own were assumed to be ‘good-time girls’ or prostitutes, especially around Brasserie Universelle at Piccadilly, popularly known as the Universal Brothel, frequented by British and U.S. airmen.

We think now of the bright lights of Piccadilly, but back then, on a winter’s night, the darkness was pervasive. Still, revellers picked their way through the rubble to dance at jazz clubs. ‘When a bomb hit the Cafe Royal, a nurse tended to the wounded amid the carnage,’ says Rubenhold. ‘While she did so, someone stole her handbag. Others stole rings from corpses.’

Crime rocketed during the war. Shortages of everything meant it was boom time for black-marketeers, and the chaos of bombing provided cover not just for murderers, but thieves, too. Rubenhold says: ‘The image we have is of great community spirit, everyone pulling together, and that is true, but it wasn’t always like that.’

Like Rubenhold’s previous podcast series — based on her book, The Five, about the women murdered by Jack the Ripper — the Blackout Ripper focuses on the victims rather than the murderer.

Rubenhold believes that studying their lives gives us an intriguing ‘snapshot’ of the times.

She and criminologist Alice Fiennes spent months combing through thousands of yellowing pages in the National Archives, looking at witness statements, fingerprint records and diaries, piecing together what they can about the women — Evelyn Hamilton, Evelyn Oatley, Margaret Lowe, Catherine Mulcahy, Doris Jouannet and Greta Haywood — who were unfortunate enough to encounter Cummins in the darkness of wartime London.

What they found was deeply unsettling. ‘This was a world far removed from the cosy myths of ‘the greatest generation’,’ says Rubenhold. ‘It was a world in which women had as much reason to fear men in Allied uniforms as they did the enemy.’

Women were routinely subjected to sexual harassment and, if they wanted to get on in the workplace, were expected to put up with unwanted male attention without complaint.

Daily Mail photographer Herbert Mason’s famous picture of St Paul’s Cathedral rising unscathed through the flames of the Blitz

Travelling or walking at night alone, they were regarded as fair game and vulnerable to rape. There was no social security, so women who did not work depended on men for money.

At the same time, the turmoil of war created conditions ripe for sexual licentiousness. Men posted far from home found solace in the company of showgirls and ‘hostesses’ in Soho.

Single women, or those whose husbands or boyfriends were away fighting, sought a protector, a source of income or a partner. (Evelyn Oatley, the second woman killed, was said to be soliciting men because she had become afraid of sleeping alone during the Blitz.)

At first glance, Cummins must have seemed a good bet for any of those roles, though the RAF pilots he trained with instinctively knew he was a phoney: they laughed at his airs and graces, referring to him as The Duke behind his back.

Cummins claimed to be the illegitimate son of a peer, living on an allowance from his aristocratic father. In reality, his affluent lifestyle was funded by petty theft.

The airman was charming and good-looking, with piercing eyes. Yes, he could be irritating, with his insistence on being referred to as the Honourable Gordon Cummins and his over-refined ‘Oxford’ accent, but he seemed harmless enough.

The year after he enlisted, he met and married Marjorie Stevens, who worked as a secretary to a West End theatre producer.

In November 1941 he was sent briefly to Cornwall, where he joined the Blue Peter, a social club where he helped behind the bar — until the landlady realised he was giving free drinks to RAF colleagues and that jewellery was missing from her flat. She suspected Cummins, but had no proof he was the thief.

Even she, surely, could not have guessed at the cruel heart beating under his uniform. The murders, which have also been revisited in a book, The Blackout Ripper by Stephen Wynn, began on February 8, 1942, after Cummins was posted to an RAF unit based in London’s Regent’s Park.

The night he killed Evelyn Hamilton, Cummins visited his wife at a flat she was renting in Southwark, South London, and borrowed a £1 note (worth about £50 today), telling her he was going to the West End for a ‘night on the town’.

Evelyn Oatley was next. Her horribly mutilated body was found little more than a mile away in her flat in Soho. She had been beaten and strangled until she lost consciousness. Her throat was cut and her abdomen, genitals and legs had been slashed with a razor blade and a tin opener.

Detective Superintendent Fred Cherrill, a pioneer in fingerprinting, examined the scene but no match for the prints he found could be made with those held by the police: the killer had no record.

Witnesses said Oatley had been approached by a young airman in Soho the previous evening. When she asked him what his sexual preferences were, he replied: ‘I like blondes.’ Oatley worked as a nightclub hostess under the name Lita Ward and supplemented her income with prostitution.

Cummins, with his slight build and cut-glass accent, must have seemed a reassuringly safe client. A woman called Ivy Poole, who rented a room in the same building as Oatley, saw her heading upstairs with a man at about 11.40pm.

She heard nothing more until after midnight, when the music on Oatley’s wireless was, strangely, turned up. Her body was found the next morning by men who had come to read the meters.

The next night, Margaret Lowe was murdered in Marylebone. Lowe, 43, was a widow whose daughter, Barbara, 15, was at boarding school. Lowe did whatever she could after her husband died to pay the school fees and make ends meet. She worked as a house cleaner — and sold sex.

Her neighbours called her The Lady because of her refined manner. She resumed her role as middle-class mother every third weekend when Barbara came to visit.

A German air raid over over central London during the Blitz in 1940

Sadly, it was Barbara who found her, having been told her mother had not been seen ‘for two or three days’. Lowe had been strangled with a silk stocking or scarf. Her abdomen had been cut open, exposing her intestines. On the right side of her groin was ‘a deep, gaping wound’. A wax candle had been inserted into her vagina.

The evening after her murder, Cummins picked up 25-year-old Catherine Mulcahy, handing over her £2 fee in advance. Mulcahy lit her gas fire but it was a cold night — so bitter she kept her boots on as she undressed to keep her feet from touching the chilly floor.

When Cummins tried to overpower and strangle her, she was able to kick him away and run screaming to a neighbour. He followed, saying he’d had too much to drink and pressing more money on her before making a swift exit. But he left his RAF belt behind.

Doris Jouannet was married but her husband travelled for work and she liked to earn money when he was away. A few hours after Cummins had attacked Mulcahy, Doris crossed his path and agreed to take him to her flat in Paddington.

The next night her husband Henri arrived home to find the bedroom door locked. He called the police. Jouannet, 32, had been strangled with a stocking. Her jaw was broken and she had been mutilated.

The police — and Press — had by now cottoned on to the fact that a serial killer was stalking London’s streets, but the story came to a sudden stop.

Following Jouannet’s murder, Cummins bought a drink for a young woman called Greta Haywood at the Brasserie Universelle.

When they left, Haywood said, Cummins became ‘unpleasantly forward’. She protested and struggled as he pushed her into a doorway, where he choked her until she lost consciousness. But he was disturbed by a delivery boy and fled, leaving his gas mask and haversack, printed with his service number — 525987 — behind.

When his room at his base was searched, several sickening ‘keepsakes’ were found: a pen belonging to Jouannet and cigarette cases belonging to Oatley and Lowe. The money he gave to Mulcahy was traced to his RAF pay packet. For technical reasons, Cummins was tried only for the murder of Oatley. The jury took just 35 minutes to convict him. He was hanged in June 1942 amid an air raid.

That Cummins has largely been forgotten is a source of satisfaction to Rubenhold: she dislikes the way serial killers acquire ‘rock star’ status, while victims barely figure.

The women he assaulted had one thing in common: they were all trying to make their way in a world turned upside down by war. ‘They faced the same danger from the bombs as men but the upheaval affected them disproportionately,’ says Rubenhold.

War had turned old moral and social order on its head. While women like Hamilton were able to rise from poor backgrounds to make careers — as she did in pharmacy — genteel women such as Lowe could be thrown into penury and forced into prostitution to keep up appearances.

Some sold sex, some didn’t, but their life stories, meticulously explored in every episode of The Blackout Ripper, create a compelling portrait of the time.

Source: Read Full Article