Post Office concealed prosecutions of hundreds of innocent postmasters

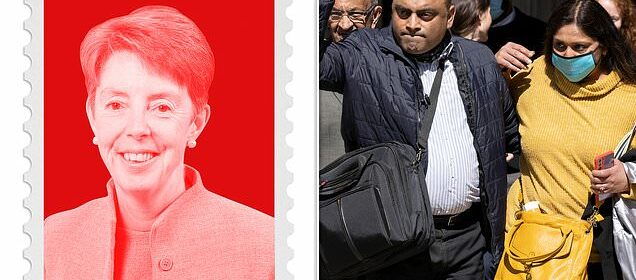

Meet Paula Vennells: As chief executive officer of the Post Office, she presided over an organisation that covered up the prosecutions of hundreds of innocent postmasters for fraud, yet Vennells left in 2019 with a bonus of almost £400k and a CBE…

- Most of the wrongly convicted victims have yet to receive a penny in compensation

- READ MORE: Post Office prosecutors investigating sub-postmasters in Horizon scandal used racial slur to classify black workers

On 11 December 2020, the day former sub-postmaster Vipin Patel’s conviction for fraud was overturned in Southwark in London, I took the train to Oxfordshire to meet the family in Horspath.

They had taken the unusual step of closing their shop for the morning so they could support Vipin in court, where earlier I’d been the only journalist to witness his acquittal.

When they arrived home in the afternoon there was a queue of schoolchildren waiting outside.

Vipin’s wife Jayshree handed out free chocolate and posed for celebratory photos as a stream of villagers came by to wish the Patels well.

At the back of the shop, I saw the closed Post Office counter, a silent monument to the family’s misery.

Paula Vennells, the Post Office chief executive from 2012 to 2019, has yet to be called as witness but is expected to give evidence in the coming months

Vipin showed me inside, indicating the position of the long-removed computer system, Horizon. ‘I am a third-generation postmaster,’ he told me. ‘In my wildest dreams I would not believe the Post Office would do anything like this.’

That day was a turning point in a scandal now acknowledged as the most widespread miscarriage of justice in British legal history.

I stumbled across this story in 2010 when a taxi driver told me tearfully that his pregnant wife – another sub-postmaster – had been imprisoned for a crime she didn’t commit.

It was an appalling case but, as I was to learn, not the only one. Over the next ten years, I discovered that more than 200 people had been sent to prison based on evidence from Horizon, a suspect Post Office IT accounting system.

To expose the story, I worked with Private Eye, made two Panorama programmes and presented a BBC Radio 4 series called The Great Post Office Trial, about the sub-postmasters’ campaign.

Vipin, the former sub-postmaster at Horspath Post Office and Stores, had been fighting for nearly a decade to clear his name.

Terrified of being sent to prison, in 2010 he pleaded guilty to fraud when he couldn’t explain a £34,000 hole in his branch accounts (he maintains the discrepancy was £70,000, £45,000 of which he had repaid through cashing in his Royal Mail pension, selling his wife’s jewellery and putting in his own money).

Receiving a suspended sentence, within a few weeks the stress had rendered him ‘comatose’ and for five days he was unable to walk, eat or even drink.

Vipin suffered permanent nerve damage and, in 2015, the resultant anxiety and loneliness made him suicidal. Now 69, he is still on antidepressants.

While also being the cornerstone of many British communities, sub-postmasters are self-employed agents of the Post Office, a public corporation owned by the government.

They are legally required to account for the public money which is processed through their branches.

In 2000 the Post Office rolled out the Horizon accounting and point-of-sale IT system, built by the Japanese company Fujitsu, to every Post Office in the country.

But the software was so badly written that it couldn’t even add up, a fact the Post Office refused to recognise.

When holes in branch accounts appeared, the postmasters were required to ‘make good’ the discrepancies with their own money or face immediate suspension, dismissal or worse.

The taxi driver who approached me in 2010 was called Davinder Misra. Seema, his wife, was the operator at West Byfleet Post Office in Surrey, and £74,000 was supposedly missing from her branch.

She was charged with theft and sentenced to 15 months in jail on her eldest son’s tenth birthday. When I spoke to Davinder, he was in bits, but also resolute. Seema’s prosecution, he told me, was far from a one-off.

He directed me to a 2009 Computer Weekly investigation by a reporter called Rebecca Thomson. This was the first piece of journalism to raise questions about the Post Office IT system.

Davinder also told me about Alan Bates, founder of a campaign group called the Justice for Sub-postmasters Alliance.

I spoke to Bates, a former sub-postmaster at Craig-y-Don in North Wales who had been sacked by the Post Office in 2003 in a dispute over accounting discrepancies at his branch.

He had IT experience before buying a Post Office and was convinced there was something wrong with Horizon.

He’d been gathering evidence from fellow sub-postmasters for seven years. He told me there could be hundreds of people around the country like Seema, who had been convicted with IT evidence from a computer system that simply didn’t function as it should.

Former Post Office sub-postmaster Seema Misra walks with her husband Davinder from The High after being cleared of theft from the Post Office

Eventually we discovered that, over a 13-year period to 2013, the Post Office successfully prosecuted more than 700 people using evidence from its Horizon IT system. Not all went to prison, but the criminal conviction ruined them.

This was phase one of the scandal. Phase two was the cover-up. In 2013, the campaign by Bates’s sub-postmasters and their constituency MPs forced the Post Office to commission a report into the IT system.

Independent investigators found errors in Horizon and roundly criticised the Post Office’s punitive business practices, including its apparent ‘prosecution bias’ and failures ‘to seek the root cause of reported problems’.

The Post Office chief executive, the Reverend Paula Vennells, ordered a series of internal reports into the prosecutions and the Horizon system.

Those investigations found that the Post Office might have prosecuted innocent people, and that its IT wasn’t fit for purpose.

Neither independent investigation firm Second Sight, nor the campaigning sub-postmasters, nor their MPs were informed.

In 2015, Vennells told the parliamentary Business Select Committee that there was ‘no evidence’ of any miscarriages of justice. That was not true.

While the cover-up was in full swing, the Post Office rubbished Second Sight, misled journalists and continued to dismiss the complaints of campaigning sub-postmasters.

The Liberal Democrat and then Conservative ministers who ran the Business department during this period seem to have been asleep at the wheel.

The motivation for the cover-up was simple: the Post Office had bet the farm on Horizon.

Any suggestion that their flagship IT system was unreliable could put off the banks, energy companies and government departments who channelled millions of pounds through the system every month.

Vennells, who was paid more than £500,000 a year throughout her tenure, had been given one job by her government masters: to make the loss-making Post Office profitable.

She did so, ignoring the cries from a growing number of sub-postmasters, leaving in 2019 with a CBE, a £389,000 bonus, the chairmanship of a large NHS Trust and a seat on the Cabinet Office Board.

The fiction maintained by Vennells during her time in office was blown apart in 2019, when more than 500 campaigners took the Post Office to the High Court over the way they had been treated.

The epic litigation was characterised by the judges’ castigation of the conduct of the Post Office throughout their pursuit of the sub-postmasters through the criminal courts:

‘The failures of investigation and disclosure were…so egregious as to make the prosecution of any of the “Horizon cases” an affront to the conscience of the court.

‘By representing Horizon as reliable, and refusing to countenance any suggestion to the contrary, Post Office Limited effectively sought to reverse the burden of proof.’

The campaigners won, triggering a series of legal developments that led to the overturning of those first convictions at Southwark Crown Court in December 2020, with a further 39 at the Court of Appeal the following year.

The Mail reported on the scandal and campaigned on behalf of the innocent men and women at the heart of the story

But what should have been a period of resolution and reconciliation has, in my view, become phase three of this scandal.

As well as having their names cleared, the surviving victims (there have been four suicides) demanded proper redress.

An initial compensation scheme was open for a few months during the worst of the pandemic. It was massively over-subscribed.

In 2021 the Post Office admitted that meeting all the claims against it would make it insolvent. It went cap in hand to the government, asking the taxpayer to step in and pick up the bill.

The government, faced with the collapse of the Post Office network, reluctantly agreed.

It has now set aside more than £1 billion to fund the various compensation schemes, but the time it has been taking for offers of redress to come through has become fatally slow.

I was contacted recently by Will Harrison, the son of one of the successful High Court claimants. Will told me his mum Sam had died in May this year without receiving proper compensation.

Sam Harrison used to run the Nawton Post Office in Ryedale, North Yorkshire. She was suspended and sacked over a discrepancy in her accounts and died at 54 after a three-year battle with cancer.

When I asked him who was to blame for the torment people like his mother faced, Will had no doubt. ‘I really despise Paula Vennells,’ he told me. ‘I think it’s disgusting that she won’t ever get really held to account.’

We know at least 61 sub-postmasters waiting for compensation have died without proper redress. Many continue to fight.

In October last year, Francis Duff, an 81-year-old former sub-postmaster, was offered £330,000, but the Post Office withheld £322,000 to settle his bankruptcy (caused by the Post Office) and pay tax on his award.

Duff was left with £8,000 and the conclusion that he’d ‘been shafted twice’.

Lawyer Dan Neidle was so scandalised by Duff’s case that he began investigating one of the Post Office’s compensation schemes.

Neidle concluded it is over-complicated and deliberately misleading.

He has made a formal complaint to the Solicitors Regulation Authority over the role the Post Office’s City lawyers Herbert Smith Freehills played in framing sub-postmaster compensation offers as confidential, something Neidle calls an ‘attempt by the Post Office to intimidate postmasters into silence’.

A public inquiry has been set up. Last year we discovered that in the late 90s, when the Horizon system was still in development, senior Fujitsu executives in Japan told the Prime Minister Tony Blair that cancelling the project would be a public-relations disaster for UK plc.

Despite formal warnings that it didn’t work, Blair issued a personal instruction to keep the Horizon project alive.

As the public inquiry enters its second year, a series of former government ministers, civil servants, Fujitsu executives and Post Office middle-managers have now given evidence, each witness carefully passing the buck up, down and around the chain of accountability. It is a depressing sight.

Paula Vennells has yet to be called as witness but is expected to give evidence in the coming months.

In a statement, Vennells said: ‘I am truly sorry for the suffering caused to the 39 sub-postmasters as a result of their convictions which were overturned. I… intend to focus fully on working with the ongoing government inquiry to ensure the affected sub-postmasters and wider public get the answers they deserve.’

Nick Read, Vennells’s successor as Post Office CEO, appears to have picked up where she left off.

Despite presenting himself as a new broom, Read concocted a bonus scheme that saw him (and around 50 other senior executives) handsomely rewarded for fulfilling the Post Office’s legal obligation to co-operate with the public inquiry.

As YOU went to press, 48 of those people had been asked to repay a proportion of this but only on a voluntary basis.

Paul Gilbert, a lawyer and leading legal ethicist, described the whole bonus-scheme affair as: ‘irredeemably rotten.

‘For someone to even have the idea of monetising the inquiry is shocking. For everyone else to go along with it shows a vacuum of dignity and decency.’

To compound matters, the Post Office declared in its annual report that the independent chair of the public inquiry, Sir Wyn Williams, had approved the bonus scheme. Neither Sir Wyn nor the inquiry were aware of it.

Read offered a grovelling apology and handed back a yet undeclared portion of his £455,000 taxpayer-funded bonus.

Read has recently found something else to apologise for. After bonusgate came the revelation that while it was falsely prosecuting its sub-postmasters, the Post Office was also racially profiling them.

A 2008 compliance document required security team investigators to divide suspect postmasters into categories including ‘negroid types’.

The scandal in numbers

More than 11,500 Post Office branches in Britain

736 sub-postmasters unsafely prosecuted for fraud or theft

4sub-postmasters took their own lives

2,500 sub-postmasters have applied for compensation from the Post Office

777 sub-postmasters have received compensation from the Post Office

61 sub-postmasters have died before receiving compensation from the Post Office

£17.5 million Post Office has paid out so far compensating overturned convictions

£4.5 MILLION Paula Vennells earned during her seven-year Post Office tenure

£32 million spent by the Post Office trying to prove there was no fault in its IT system

£100 MILLION spent by the Post Office on City lawyers

£1,200 Maximum the Post Office has contributed to any sub-postmaster’s legal fees

ZERO – punitive damages

Last month, Read sent an all-staff email to his racially diverse cohort of 7,000 sub-postmasters.

‘I know that you will not only be upset but also very concerned that such language was being used within the Post Office,’ he wrote.

‘While a lot of progress has been made in ensuring that our culture is inclusive… we know there is still a lot more for us to do and we must continue our efforts.’

The speed at which the criminal justice system is moving to quash convictions seems to have ground to a halt.

No fewer than 600 convictions, secured on the back of Horizon evidence, are believed to be potentially unsafe.

Six were quashed in 2020, 66 in 2021, 12 in 2022 and so far in 2023 only two, making a total of 86. Kevan Jones MP has called this ‘extremely concerning’.

Last December – two years after Vipin’s conviction was quashed – Post Office lawyers offered him £200,000. (They were talked up from their initial offer of £100,000.) Vipin called it ‘derisory’.

His son, Varchas, reminded me that the couple wrongfully arrested over the Gatwick drone disruption were given a £200,000 settlement.

He asked how it could compare to a man whose health and finances were ruined by a wrongful conviction.

Last month, Vipin had a mini-stroke. He remains in pain, at home. With nothing to fund his retirement, he still runs Horspath Stores with Jayshree.

Vipin worries about her having to work more hours at their shop. ‘It is always at the back of my mind,’ he says.

While Vennells is free to enjoy her huge Post Office payoff and early retirement, I wonder just how much time Vipin and so many other victims of this scandal have left.

Source: Read Full Article