The two-party system is cooked, and the Liberals are leftovers

There is a grim set of numbers connecting the three coalition governments thrown out of office over the past 12 months to the Labor regimes that replaced them. It is the historically low primary votes for the main parties – regardless of location, length of incumbency, or popularity of leaders.

The defeated conservative governments recorded near-identical primary votes: 35.7 per cent for the Liberals at the South Australian state election in March 2022, 35.7 per cent for the Coalition at the federal election in May 2022, and 35.4 per cent for the Coalition at last month’s NSW state election.

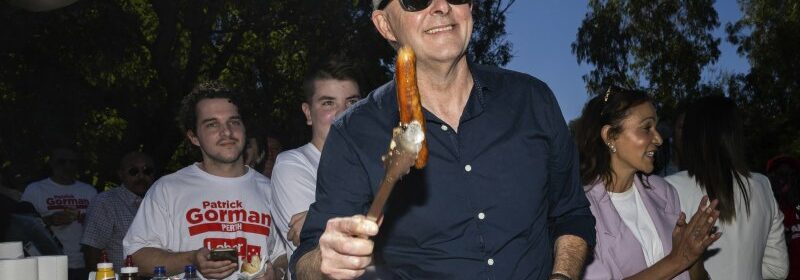

Recent elections have shown the two-party system is officially cooked.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

But Labor did not get above 40 per cent in its own right in any of its successful campaigns. Only Peter Malinauskas and Labor took power decisively in South Australia with a primary vote of exactly 40 per cent, and a two-party vote after the distribution of preferences of 54.7 per cent. Anthony Albanese secured a majority of just two seats with a primary of 32.6 per cent, and a two-party preferred vote of 52.1 per cent, while Chris Minns fell short of a majority in NSW with a primary vote of 37 per cent and a 2PP of 53.7 per cent.

The two-party system as we knew it in the 20th century, when a new government started with a primary vote of around 50 per cent, and its opponent still had a base in the low 40s, is officially cooked.

But it is the federal and state Liberals who are now facing an existential threat, with predominantly white and male party rooms. The Liberals are the least representative “major” party that the federal parliament has seen; a factor reinforced by the loss of former blue ribbon Liberal electorate of Aston, in Melbourne’s outer east, last Saturday.

The party of Robert Menzies is outnumbered 26 to 30 in the lower house by their coalition colleagues from the Queensland LNP and the National Party. And the 10 city-based Liberals outside Brisbane are matched by the 10 independents and Greens.

Labor, on the other hand, can afford a record low entry vote into power because it has proven, at a state level at least in the 21st century so far, that it knows how to turn narrow first-term wins into second- and even third-term landslides.

Peter Dutton should understand this dual equation – the vulnerability of his own side to the great shifts in Australian society, and the precedent on the Labor side for a decade-long rule across the national and big state parliaments following an era of divisive Coalition governments.

The loss of Aston was catastrophic not merely because it was the first time since 1920 that a federal government had picked up a seat from an opposition at a byelection. It is because Victorians have done this to the Liberals before at state level.

When Steve Bracks led Labor into minority government in 1999, there was an assumption that the Coalition would be competitive at the next state election because it no longer had the one-man drag on their vote – former premier Jeff Kennett. Insert Scott Morrison in Kennett’s place and you can appreciate why the Albanese government will be wargaming another byelection upset if and when the former prime minister resigns from his southern Sydney electorate of Cook.

Labor won the byelection for Kennett’s seat of Burwood, in Melbourne’s middle east, in 1999, and then the byelection for the former National Party leader and deputy premier Pat McNamara’s rural seat of Benalla in 2000. Neither had ever been held by Labor before, and while Benalla returned to the Coalition fold in 2002, Burwood remained in Labor hands during the next two Brackslides in 2002 and 2006. Today, it is part of the new seat of Ashwood, which Labor won with a primary vote of 40.3, and a 2PP of 56.2 per cent, at last November’s state election landslide for Daniel Andrews’ government.

Dutton may not have bothered with the finer details of Victorian state politics when he was a rising star in John Howard’s Coalition government. But Bracks is the leader who is closest in manner, and underestimated political appeal to Albanese. Neither are white Anglo men. Bracks has Lebanese heritage; Albanese is half Italian. Neither man is consciously ethnic; in fact, they are routinely surprised when constituents share stories from homelands to which they themselves have no direct connection. Bracks and Albanese have diversity projected onto them. It is innocent in many ways. But in the head-to-head between Albanese and Dutton, in a nation that is majority migrant now, it matters more than the latter probably appreciates.

Dutton is already sick of hearing the advice from his own side that the Liberals have a problem with female voters, with young Australia who can’t afford to enter the housing market, and with migrant communities, especially Chinese Australians whom he helped alienate with his war talk.

But there is a structural paradox that he and his colleagues ignore at their peril. It is inevitable that diversity will accelerate in every state.

Illustration by John Shakespeare.Credit:

Take a step back from the slicing and dicing of the electorate by cohorts and consider the basic question of population growth, through the concept of the Australian family tree, with First Australian roots, an Old Australian trunk and New Australian branches. The trunk represents non-Indigenous people who were born in this country, as were their parents and grandparents, while the branches cover migrants and their locally born children.

At the 2021 census, New Australia formed the majority with 50.8 per cent of the then population of 25.4 million; Old Australia was 45.4 per cent and First Australia 3.8 per cent. Almost two years on, the population is one million larger and the branches and the roots will have increased their respective shares at the expense of the slower-growing trunk.

We know this because of what happened in the boom years before lockdown. Migrants were responsible for the majority of the nation’s population growth for the first time since the gold rushes of the 1850s.

Migrants accounted for 60 per cent of Sydney’s population growth and 54 per cent of Melbourne’s between 2011 and 2021. In Darwin, it was 62 per cent, Hobart 55 per cent, Canberra 46 per cent, Adelaide 44 per cent and Perth 42 per cent. Brisbane was the outlier at 39 per cent because it had a more even mix of growth thanks to internal migration. Yet once you add the children of migrants, 69 per cent of the growth in the Queensland capital came from New Australia. In Sydney, the figure was 97 per cent; Melbourne 88 per cent and Perth 75 per cent – the three key cities from which the Liberals were evicted by Labor and the teals at the last federal election.

Australia, seen through Dutton’s LNP binoculars in Brisbane, looks like another country. But even Brisbane is moving closer to the cosmopolitan south. Remember that Greens picked up three seats here – two from the LNP and one from Labor. They did this in the whiter parts of the city where young professional renters are moving the pendulum to the left.

The most brazen aspect of Dutton’s decision this week to lock in the LNP and Liberals to a No vote on the referendum for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to parliament is the attempt to shake the leaves of our family tree. Migrant communities are among the key swinging voters in the referendum – soft Yes voters, according to the public and private polls, who could be persuaded to vote no if change is seen as too risky, or complicated.

What Dutton seems to have forgotten is that Howard himself took an equivalent dark path as opposition leader in the late 1980s when he criticised Asian migration. It cost Howard the Liberal leadership at the time, and placed a personal re-entry barrier to the job which he finally cleared in 1995 by apologising for his comments. Howard helped make the Liberals electable again by dropping his ideological baggage on Medicare, industrial relations and migration. He met the electorate on its terms, while articulating a positive agenda around core Liberal values.

Where is the equivalent work being done by Dutton and his colleagues, either federally, or in basket case states or Victoria, South Australia or Western Australia?

On the evidence so far, Dutton believes he has nothing to learn. He went to work immediately after the Aston debacle determined to double down on the politics of division that helped make the Liberals a minor party across large parts of the country.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article