How a Labour council brought the stamp of a jackboot to a British city

Police raids at 5am, pensioners handcuffed and held for eight hours and false accusations of poisoning tea: GUY ADAMS investigates the devastating impact of Labour-run Sheffield council’s totally nonsensical axing of thousands of trees

- Sheffield City Council abandoned the plan in 2018, with 5,600 trees removed

- The council spent £300,000 trying to stop local demonstrations against the plan

The police came at five o’clock one Thursday morning, banging on doors to inform bleary-eyed homeowners that they needed to get out of bed and move their cars.

Residents who failed to comply were swiftly punished: within minutes, around ten vehicles were loaded on to lorries and towed away, past road blocks that now prevented access to either end of the street.

Inside this cordon, dissent was crushed. Three people who took umbrage at the pre-dawn raid were slapped in handcuffs, including a thirtysomething man and two grandmothers in their early 70s.

The elderly duo, a retired sociology professor called Jenny Hockey, and her neighbour Freda Brayshaw, a former teacher, were driven to the police station for questioning. It would be eight hours before they were released.

‘Our street was seething with people — lights, noise, chainsaws,’ was how Hockey recalled her arrest. ‘The whole thing was just horrific.’

Residents who failed to comply were swiftly punished: within minutes, around ten vehicles were loaded on to lorries and towed away, past road blocks that now prevented access to either end of the street

‘Our street was seething with people — lights, noise, chainsaws,’ was how Hockey recalled her arrest. ‘The whole thing was just horrific’

The date was November 17, 2016. And the events unfolding on Rustlings Road, a residential street in south-west Sheffield, would dramatically escalate a hugely bitter dispute, turning the Yorkshire city — or rather, its Labour-run council — into a globally recognised symbol of incompetence, mendacity and tin-pot authoritarianism.

That status was confirmed this week with the publication of an official report laying bare how Left-wing politicians and their senior officials behaved with brazen dishonesty, repeatedly lying to the public during the long-running and, at times, utterly surreal affair.

Sheffield’s bizarre civic war revolved around the city’s trees. Or rather, a flawed plan by the council to chop down around half of them, for no good reason at all.

It kicked off in 2012, when councillors signed a 25-year, £2.2 billion Private Finance Initiative (PFI) deal that handed management of local streets to a Spanish-owned infrastructure firm called Amey. The contract, written by officials who had misinterpreted expert advice, stipulated that duties would include destroying 17,500 mature and often historic trees and replacing them with saplings.

Locals took umbrage and began protesting. The council responded with staggering autocracy and dishonesty, attempting to cover up details of the flawed scheme. Perhaps inevitably, things escalated. As so often, in the broken world of local government, not one of the many Labour councillors singled out for criticism in the utterly damning report has so far chosen to resign. Indeed, two —Terry Fox and Bryan Lodge — have been promoted and are now gleefully running England’s fourth largest city.

And while a series of grovelling apologies was issued this week, not a single council employee or any of its highly paid executives has been either disciplined or sacked. Two architects of the costly shambles, former chief executive John Mothersole and a senior official called Paul Billington, are instead enjoying prosperous retirements.

All of which brings us back to Rustlings Road, where eight towering limes had been shading local front gardens for more than 100 years. Sheffield City Council claimed they were nearing the end of their natural life and had roots that were damaging the pavement. Many locals disagreed.

Research by conservationists had raised questions, meanwhile, about the process whereby the limes were selected for destruction. It established that City Hall jobsworths had misidentified one of the doomed trees as a sycamore, and wrongly classified it as diseased when it in fact had no visible sign of any fungus.

An independent panel, convened by the council, agreed with residents, concluding that the Rustlings Road limes should be preserved. But bovine city bigwigs, who seemingly resented having their authority challenged, decided to bring in the chainsaws anyway.

They chose to turn up at 5am to lessen the chance of protests on the street, where handsome Victorian houses fetch up to £850,000. Anyone who, like Hockey and Brayshaw, attempted peacefully to disrupt them was arrested under Thatcher-era laws designed to prevent flying pickets.

The tactic meant that seven of the eight Rustlings Road limes were toppled by daybreak, when heavy rain stopped play. But what the Labour officials hadn’t expected, while cooking up the anti-terror-style raid, was the angry response it would provoke.

Local MP Nick Clegg, formerly Britain’s deputy Prime Minister, rightly compared the whole thing to ‘scenes you’d expect to see in Putin’s Russia rather than a Sheffield suburb’. Then Defra Secretary Michael Gove accused the ‘bonkers’ council of ‘wanton ecological vandalism’.

Protests followed across the city, with increasingly febrile groups of activists starting to mount round-the-clock vigils to prevent other trees from being destroyed.

The whole shambles, which lasted another 16 months, saw 41 people arrested. Dozens more were dragged through the courts as the increasingly desperate council, which was already spending a fortune on private security guards, forked out another £300,000 trying to use draconian injunctions to stop demonstrations.

At one point in 2017, Sheffield even attempted to have an opposition councillor, the Green Party’s Alison Teal, thrown into prison for allegedly breaching one such injunction by attending a protest. The banana republic-style case was thankfully chucked out.

In a surreal incident the following year, detectives searched the home of a retired health and safety inspector named Dr John Unwin and his architect wife Sue amid claims that they’d served poisoned cups of tea to workmen attempting to remove trees outside their Victorian home in Dore.

The claims were, of course, rubbish. ‘Poisoning people’s tea sounds like a plot from an Agatha Christie novel or something involving a Russian dissident,’ said John, who insisted they’d merely served normal drinks as a ‘delaying tactic’ to frustrate the felling work.

By the time Sheffield council came to its senses in March 2018, and abandoned the scheme, around 5,600 trees had been removed, at a cost of tens of millions of pounds, while their administration had become a global laughing stock.

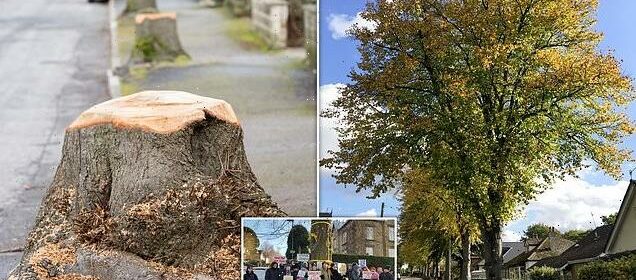

Dozens more were dragged through the courts as the increasingly desperate council, which was already spending a fortune on private security guards, forked out another £300,000 trying to use draconian injunctions to stop demonstrations. Pictured: Before

By the time Sheffield council came to its senses in March 2018, and abandoned the scheme, around 5,600 trees had been removed, at a cost of tens of millions of pounds, while their administration had become a global laughing stock. Pictured: After

This week’s forensic, 200-page independent inquiry by Sir Mark Lowcock details the depths to which senior employees and councillors sank during this ugly period, revealing how officials ‘repeatedly said things that were economical with the truth, misleading, and in some cases were ultimately exposed as dishonest’.

‘Some of the things the council did were, in the view of the inquiry, unacceptable. Some of the ideas it flirted with, but did not pursue, were worse,’ he writes. The saga began in the late 2000s, when Sheffield had earned the nickname ‘pothole city’ on account of its unrepaired streets, and the local press was running a ‘City of Darkness’ campaign because of failed streetlights.

Blair-era reforms meant large pots of funding were available to local authorities who signed PFI deals that brought in supposedly efficient private firms to run public infrastructure. So Sheffield cooked up a 25-year scheme called Streets Ahead, to improve its roads and pavements.

Before they invited bids, a surveying firm was brought in to analyse the city’s 35,000 or so trees. It reported around 74 per cent of them to be either ‘mature’ or ‘over-mature’. Sheffield council therefore told bidders for the PFI scheme that a ‘large proportion’ of these trees needed to be replaced, and stipulated that 17,500 should be chopped down during the course of the contract.

This requirement was, to paraphrase the report, utterly bonkers. Why so? Well, for reasons that remain unclear, bungling council officials had misinterpreted the surveyor’s report, which had actually found that only 1,000 trees needed to be replaced.

A tree classified as ‘mature’ has merely reached full height, while one that is ‘over-mature’ is continuing to grow, but remains productive and can thrive for many decades. In other words, there’s no reason to touch it. Having made this fatal error, the council failed to foresee that residents who witnessed thousands of perfectly healthy trees being needlessly destroyed, in a city famed for its greenery, might react angrily.

Instead, councillors began provocatively smearing opponents as entitled Nimbys. Party politics was at least partly to blame: the leafiest parts of Sheffield, where much of the tree-felling was concentrated, were in the relatively prosperous south and west of the city, which tended to vote Lib Dem. But at the time the PFI deal was signed, the council was under Labour control, thanks to their opponents’ unpopularity during the Coalition years.

‘Absolute power was the problem,’ is how Shaffaq Mohammed, leader of the city’s Liberal Democrats, now puts it. ‘They had 59 or 60 seats out of 84 on the council, so could do what they wanted and the attitude was, “How could middle-class Nimbys in posh houses in the west of the city resist us?” It became a sort of class war.’

This culture of contempt for taxpayers — there’s really no other way to describe it — served only to inflame tensions, with matters turning nuclear following the events on Rustlings Road in 2016.

By this point, protesters were using WhatsApp groups and social media networks to gather on streets where trees were scheduled for felling to block work. They used a variety of techniques, including ‘bunnying’, or hopping over barriers erected around targeted trees, and ‘geckoing’, standing next to garden walls and refusing to move.

The council responded by pursuing litigation rather than reconciliation. It chose to take purported ringleaders to court.

One of those prosecuted, a professional magician called Benoit Compin who was prosecuted for climbing a tree scheduled for destruction, is still being pursued for £13,500 today.

‘I cannot afford to pay, but even after everything they have had to apologise for, they are still trying to make me,’ he tells me.

During this period, Labour councillors repeatedly denied that 17,500 trees were being chopped down under the PFI deal, claiming falsely that no target existed. When campaigners used Freedom of Information (FOI) laws to seek disclosure of key documents that might prove they were lying, the council claimed they were ‘commercially sensitive’. After the Information Commissioner ruled that they should nonetheless be released, they changed tack, claiming paperwork had been ‘lost’.

Only when staff mysteriously ‘stumbled upon’ lost documents in 2018, was the 17,500 figure belatedly made public. Even then, officials denied there was a real target, until other emails emerged showing that Paul Billington, the senior official who oversaw the tree-chopping scheme, threatened to levy penalties — believed to be around £3 million — against infrastructure firm Amey if it missed quotas.

Among those responsible for this culture of deceit was Terry Fox, the councillor who had responsibility for the scheme in 2016.

Back then, he said: ‘We are not removing 18,000 trees as the campaigners have been suggesting. We look after 36,000 street trees and will remove and replace around 14 per cent.’ Today, Councillor Fox is Labour leader of Sheffield council. Issuing a grovelling apology, this week he finally accepted that his previous statements were false. He declared: ‘I’m not going to resign. I genuinely believe eight years ago I made a real effort to get a consensus to this dispute.’

A culture of contempt for open government under Fox’s party was endemic. Early in 2016, for example, the council set up an ‘independent’ panel in an effort to review contentious tree demolitions. But its boss class then chose to ignore the panel’s advice to save trees in no fewer than 75 per cent of cases.

Elsewhere, the report tells how staff fell into the habit of doctoring emails about the PFI scheme to include a disclaimer in the subject line that wrongly stated the contents were ‘not subject to FOI’ in a cynical bid to prevent them being publicly disclosed in future.

‘Words like battle, war and conflict were increasingly used in internal conversations from 2016 onwards,’ the report says. ‘Other [witnesses] referred to the bunker mentality that developed in the council, describing a culture that was unreceptive to external views, discouraging of internal dissent and prone to group think.’

Sir Mark also found that the council misled two High Court judges during trials connected to the scheme by passively allowing them to rely on a piece of evidence it knew to be false — a misleading version of its five-year tree management strategy — and failing to correct the record.

‘While it did not affect the outcome in either case, it is still a serious matter that the court was misled,’ writes Lowcock. He added that he’d taken legal advice as to whether councillors or officials had committed perjury but decided they had not.

By early 2018, Billington, who oversaw the tree-chopping scheme, was so drunk on power that he emailed Bryan Lodge, the Labour councillor who’d taken over responsibility from Fox, to suggest the secret mass killing of healthy trees in a desperate last-ditch attempt to ‘defeat’ protesters.

The note, which bore the subject line ‘please print and then delete’ — presumably in an effort to prevent it ever becoming public — analysed the potential of using ring barking (the practice of killing healthy trees through completely removing bark around the circumference of the trunk) to get their way. It explains that: ‘The tree is killed and dies over a number of months. It would move all trees into the “dying” category and mean that [protesters] could no longer claim they were defending “healthy” trees.’ Thankfully, the grotesque scheme was never enacted.

Councillor Lodge’s behaviour was equally indefensible. In 2017, he issued a statement alleging that the council was ‘working with groups such as The Woodland Trust to ensure everything possible is being done to protect wildlife and Sheffield’s rich biodiversity’.

In an open letter reported in the Yorkshire Post, Beccy Speight, then chief executive of the Woodland Trust, responded: ‘I would like to make it absolutely clear that Sheffield City Council is not “working with” the Woodland Trust as claimed in Councillor Bryan Lodge’s letter.’

Lodge was also cited in a section of the inquiry report criticising the way the council made ‘speculative and unreliable’ estimates about the supposedly ‘catastrophic’ costs of retaining trees, rather than chopping them down. In one interview, he told the media the cost of saving them would ‘run into the millions’.

A colourful attitude towards the truth has done little to prevent this Labour politician rising to the top of Sheffield’s Left-wing political ladder. Today, he’s co-chair of the finance committee, overseeing a budget of £1.4 billion a year.

Should a man so heavily criticised in an official report continue to hold high office? Apparently so: ‘I spoke to Bryan last night,’ boss Terry Fox told reporters this week. ‘He apologises sincerely . . . He did offer his resignation. I turned it down.’

Proof that in Britain’s town halls, as in so many other areas of this saga, nothing ever succeeds quite like failure.

Source: Read Full Article