The surreal day Marilyn Monrow was handed naked portraits of herself

The surreal day a dishevelled and dazed Marilyn Monroe was handed naked portraits of herself… Then three weeks later she was dead

Two indelible images were ingrained in my mid-teen mind. The first was seeing, one blustery June day in 1953, the just-crowned Queen: youthfully pearlescent, sensitive, smiling through rain from that great ornate carriage as she passed, quite close, beside the windows of my father’s club in St James’s.

And, not very long after, having hared across those hard-won playing fields of Eton, over lanes and ditches, to the Gaumont in Slough to see, in celluloid colour, the world-heralded Marilyn Monroe in There’s No Business Like Show Business.

While an afternoon audience of housewives swooned at the gyrations of her co-star Johnnie Ray, I was enraptured by the sashaying form, the lyre-shaped arms, the wide luscious mouth — the trembling, exquisite being that was Marilyn.

These two women, born a few weeks but worlds and time and cultures apart, both young and assured and vivacious at so early a milestone in their diverse futures had, at those first coups d’oeil, an equal promise of pleasure, security and a touching similarity in their shimmering white and diamonds and radiance.

The Queen recently confided to a friend that she rather longed to be an actress if statecraft had not been her destiny. But Marilyn had to contend with the pitfalls of actually being an actress in order to become queen of a more calumniatory empire.

Too soon we were to learn of the canker in Marilyn’s crimson rose. Too soon came the revelations of a chaotic upbringing, deeply contorted emotions and betrayed trust.

We watched and wondered, for the next decade, at her sublime beauty, her innate goofiness, the promise of her pout, her glorious gaiety. There was always that nagging feeling that, deep down, almost nothing was right with, or for, her. That, despite the glamour in pink satin, the black monkey-fur, the swirling white and the desert-bleached denim, it was all, inevitably, a charade?

Marilyn had to contend with the pitfalls of actually being an actress in order to become queen of a more calumniatory empire

Too soon we were to learn of the canker in Marilyn’s crimson rose. Too soon came the revelations of a chaotic upbringing, deeply contorted emotions and betrayed trust

In celluloid colour, the world-heralded Marilyn Monroe in There’s No Business Like Show Business

Photographer Bert Stern has done a sensational shoot with Marilyn. And, what’s more, she’s agreed to be photographed naked

A few years pass and while the perfection of her image remained unchanged, one’s heart was in one’s mouth on her behalf. She’s private. She’s ill. She’s late. She’s seeing Peter Lawford, she’ll only see Natasha Lytess, her drama coach. No, she won’t see anyone; she’s a recluse.

The nearest I’d got to her up to then was one sultry Los Angeles summer night. In a bar on Hollywood and Vine, I’d picked up a leathered hunk.

Later, lazily, from his Brentwood veranda, he gestured to a one-storey across the street. ‘That’s Marilyn’s.’ He would have known: he was the singer Peggy Lee’s hairdresser.

So this is the house, pale and faded under its dusty greenery, that was to be there for the entire rocky ride, mute witness to her second husband Joe DiMaggio’s jealousy, the humiliation by third husband Arthur Miller, the ill-fated venture with photographer Milton Greene, the unborn child (by Tony Curtis), the clutches of the Kennedy cabal and reports of fiasco footage on the set of Something’s Gotta Give, her unfinished last film. A couple of Julys later, in 1962, there’s a conspiratorial but palpably joyous atmosphere in our art department at Vogue in Manhattan. On the layout pinboard among the dedicated editorial pages for the September issue, are 14 starkly white double-page spreads — no hint as to their content.

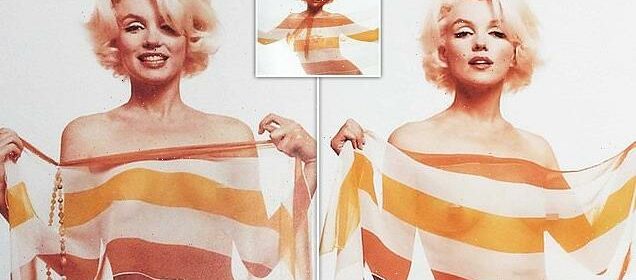

The editors, Diana Vreeland, Alex Liberman & Co, buzz around them proudly, congratulatorily, changing the order and shape with sotto voce gestures. Whatever this project is, it’s mammoth. Eventually I find out, and am sworn to secrecy: the photographer Bert Stern has done a sensational shoot with Marilyn. And, what’s more, she’s agreed to be photographed naked.

So she’s all right! She’s back!! On top!!! Everything’s gonna be OK.

The contacts come in. Exclaimed, rhapsodised, pored over . . . here she is, once again.

Glorious, restored, ravishing, the honey-dewed skin, the gold-dust shoulders, the ice-white cow-lick, the coral lips quivering. Then someone remembers she has photo approval.

There’s a conference and . . . .‘Erm, Nicky’ — Priscilla Peck, the art director, is the acme of politesse — ‘Erm, could you, erm, take these up to Miss Monroe?’ I was presented with a heavy white envelope and a red chinagraph pencil. ‘And please wait while she chooses.’

At 6.30 that evening, I ring the bell of the apartment at 444 East 57th St. Nothing. I ring again. A small dog barks shrilly; then footsteps. The door opens. The goddess is mere inches from my gaze.

Her eyes are red, her greasy face and smudgy lips framed by lank, lifeless hair. She wears a shapeless grey tracksuit with make-up stains at the neckline.

Glorious, restored, ravishing, the honey-dewed skin, the gold-dust shoulders, the ice-white cow-lick, the coral lips quivering

At 6.30 that evening, I ring the bell of the apartment at 444 East 57th St. Nothing. I ring again. A small dog barks shrilly; then footsteps. The door opens. The goddess is mere inches from my gaze

Her eyes are red, her greasy face and smudgy lips framed by lank, lifeless hair. She wears a shapeless grey tracksuit with make-up stains at the neckline

She opens the envelope and holds each contact sheet against the door, with the wax crayon expertly and unhesitatingly circling the ones she liked

She looks half-dazed, almost haunted. The dog barks again.

‘Be quiet, Maff,’ she rasps, her hand half-shading her gaze.

I held out the bulging envelope. ‘My editor has asked me to . . . ’

‘Thank you, honey, but I’m running late.’ She half-closes the door, then looked down. ‘Are they OK?’

‘Yes, they’re wonderful. Of course they’re wonderful. How could they not be?’

‘Oh, thank you, honey.’ The mascara-messed eyes looked up at me, her voice strangely remote. ‘Do you mind if we look at them right here? I’m kinda . . .’

She opens the envelope and holds each contact sheet against the door, with the wax crayon expertly and unhesitatingly circling the ones she liked, X-ing others, and, sucking her teeth, puts a pale thumbnail through total rejects.

Just as we started on the colour transparencies, a telephone rang, faint, in a distant room.

Marilyn looked panicked. The grubby, unwashed reality gathered up these last images of her golden glory in her arms, thrust them into mine and ran unsteadily back down the corridor.

The dog barked again. The telephone stopped ringing. Marilyn’s door was still open when the lift arrived.

She died three weeks later.

- This article first appeared in the August issue of The Oldie magazine.

Source: Read Full Article